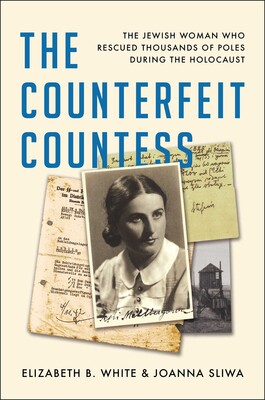

The Counterfeit Countess: The Jewish Woman Who Rescued Thousands of Poles During the Holocaust by Elizabeth B. White and Joanna Sliwa (Simon & Schuster). Reviewed by Kitty Kelley. “The authors are unsparing in describing the unrelenting and unrelieved miseries inflicted by the Nazis in decimating the Jewish population of Poland, which had the largest concentration of Jews in Europe in 1939 — 3.5 million then, fewer than 20,000 today. It becomes almost numbing to read of the killing of so many Jews, Roma (gypsies), and others at the hands of the Germans and their minions.”

The Counterfeit Countess: The Jewish Woman Who Rescued Thousands of Poles During the Holocaust by Elizabeth B. White and Joanna Sliwa (Simon & Schuster). Reviewed by Kitty Kelley. “The authors are unsparing in describing the unrelenting and unrelieved miseries inflicted by the Nazis in decimating the Jewish population of Poland, which had the largest concentration of Jews in Europe in 1939 — 3.5 million then, fewer than 20,000 today. It becomes almost numbing to read of the killing of so many Jews, Roma (gypsies), and others at the hands of the Germans and their minions.”

By the Numbers: Numeracy, Religion, and the Quantitative Transformation of Early Modern England by Jessica Marie Otis (Oxford University Press). Reviewed by Jay Hancock. “Arabic numerals were so embedded in the commercial system by 1700 that it ‘would go near to ruine the Trade of the Nation’ if merchants had to revert to Roman numerals, tally sticks, and other older systems, Otis quotes a Scottish physician and mathematician as saying. Like all good historians, though, she cautions readers against modernity bias, in this case assuming that Arabic notation seemed any more familiar to most early-modern Europeans than, say, Norse runes look to people today.”

By the Numbers: Numeracy, Religion, and the Quantitative Transformation of Early Modern England by Jessica Marie Otis (Oxford University Press). Reviewed by Jay Hancock. “Arabic numerals were so embedded in the commercial system by 1700 that it ‘would go near to ruine the Trade of the Nation’ if merchants had to revert to Roman numerals, tally sticks, and other older systems, Otis quotes a Scottish physician and mathematician as saying. Like all good historians, though, she cautions readers against modernity bias, in this case assuming that Arabic notation seemed any more familiar to most early-modern Europeans than, say, Norse runes look to people today.”

The Invocations by Krystal Sutherland (Nancy Paulsen Books). Reviewed by Nick Havey. “This is the central idea of the novel, that power — even the mere pursuit of it — corrupts. The book ends with hope for the future (Sutherland is smart to portend a sequel), but it is also cautious. As we have learned here, magic comes at a cost. And for readers, the magic that is The Invocations comes at a horrible cost: the absolutely devastating comedown one experiences after finishing a great book.”

The Invocations by Krystal Sutherland (Nancy Paulsen Books). Reviewed by Nick Havey. “This is the central idea of the novel, that power — even the mere pursuit of it — corrupts. The book ends with hope for the future (Sutherland is smart to portend a sequel), but it is also cautious. As we have learned here, magic comes at a cost. And for readers, the magic that is The Invocations comes at a horrible cost: the absolutely devastating comedown one experiences after finishing a great book.”

Our Hidden Conversations: What Americans Really Think About Race and Identity by Michele Norris (Simon & Schuster). Reviewed by William Rice. “The author reinforces a hopeful reading with her graceful, sympathetic, insightful oversight of the material. Norris, who is Black, is able to offer expert interpretation and explanation of white racism in all its myriad forms to the close-minded or ill-informed. But she displays equal-opportunity empathy for the human experience — whether suffering, frustration, or joy — regardless of the race of the person experiencing it.”

Our Hidden Conversations: What Americans Really Think About Race and Identity by Michele Norris (Simon & Schuster). Reviewed by William Rice. “The author reinforces a hopeful reading with her graceful, sympathetic, insightful oversight of the material. Norris, who is Black, is able to offer expert interpretation and explanation of white racism in all its myriad forms to the close-minded or ill-informed. But she displays equal-opportunity empathy for the human experience — whether suffering, frustration, or joy — regardless of the race of the person experiencing it.”

This New Dark: A Novel by Chase Dearinger (Belle Point Press). Reviewed by Mariko Hewer. “Dearinger’s strength is in these viscerally horrifying descriptions, which he peppers throughout the book without oversaturating it. You can almost feel the terror leaching out of the story and into reality, even as you know it’s safely contained in the pages. A later confrontation between Wyatt, Esther, Randy, and whatever it is up in the hills that’s taken the form of a cougar adds another jolt to the nightmare.”

This New Dark: A Novel by Chase Dearinger (Belle Point Press). Reviewed by Mariko Hewer. “Dearinger’s strength is in these viscerally horrifying descriptions, which he peppers throughout the book without oversaturating it. You can almost feel the terror leaching out of the story and into reality, even as you know it’s safely contained in the pages. A later confrontation between Wyatt, Esther, Randy, and whatever it is up in the hills that’s taken the form of a cougar adds another jolt to the nightmare.”

Flight of the Wild Swan: A Novel by Melissa Pritchard (Bellevue Literary Press). Reviewed by Carrie Callaghan. “But how accurate, either, are the folk legends and histories we receive through popular culture? Florence Nightingale dared to highlight the hypocrisies of her time and to subvert gender stereotypes. For her labors, history reshaped her into a paragon of sexless femininity. This novel challenges that characterization. It challenges the very idea that a person can ever be one thing, one consistent thing, and instead asks us to see the messy heart behind the headlines. Flight of the Wild Swan is a beautiful accomplishment.”

Flight of the Wild Swan: A Novel by Melissa Pritchard (Bellevue Literary Press). Reviewed by Carrie Callaghan. “But how accurate, either, are the folk legends and histories we receive through popular culture? Florence Nightingale dared to highlight the hypocrisies of her time and to subvert gender stereotypes. For her labors, history reshaped her into a paragon of sexless femininity. This novel challenges that characterization. It challenges the very idea that a person can ever be one thing, one consistent thing, and instead asks us to see the messy heart behind the headlines. Flight of the Wild Swan is a beautiful accomplishment.”

The Garretts of Columbia: A Black South Carolina Family from Slavery to the Dawn of Integration by David Nicholson (University of South Carolina Press). Reviewed by David A. Taylor. “The book also includes granular detail of how Jim Crow racism worked at the day-to-day level. Nicholson unpacks the old Columbia city directory’s designating of race — from asterisks to whole color-coded pages — as well as how some of its listings were left out entirely during the archiving process. ‘Did the microfilm operator decide on his own to omit half the city’s population?’ he asks. ‘These are the kind of uncomfortable thoughts that come dealing with such a complicated history.’”

The Garretts of Columbia: A Black South Carolina Family from Slavery to the Dawn of Integration by David Nicholson (University of South Carolina Press). Reviewed by David A. Taylor. “The book also includes granular detail of how Jim Crow racism worked at the day-to-day level. Nicholson unpacks the old Columbia city directory’s designating of race — from asterisks to whole color-coded pages — as well as how some of its listings were left out entirely during the archiving process. ‘Did the microfilm operator decide on his own to omit half the city’s population?’ he asks. ‘These are the kind of uncomfortable thoughts that come dealing with such a complicated history.’”

The Bishop and the Butterfly: Murder, Politics, and the End of the Jazz Age by Michael Wolraich (Union Square & Co.). Reviewed by Diane Kiesel. “Author Michael Wolraich has resurrected social-butterfly Gordon and the story of her improbable impact on New York’s Jazz Age corruption and vice in The Bishop and the Butterfly, a true-crime tale that reads like a novel. Although seemingly far-fetched, the fallout from Gordon’s murder, Wolraich credibly posits, helped bring down New York City’s political machine and catapult FDR into the White House.”

The Bishop and the Butterfly: Murder, Politics, and the End of the Jazz Age by Michael Wolraich (Union Square & Co.). Reviewed by Diane Kiesel. “Author Michael Wolraich has resurrected social-butterfly Gordon and the story of her improbable impact on New York’s Jazz Age corruption and vice in The Bishop and the Butterfly, a true-crime tale that reads like a novel. Although seemingly far-fetched, the fallout from Gordon’s murder, Wolraich credibly posits, helped bring down New York City’s political machine and catapult FDR into the White House.”

Medgar & Myrlie: Medgar Evers and the Love Story that Awakened America by Joy-Ann Reid (Mariner Books). Reviewed by Paul D. Pearlstein. “Now 90, Myrlie still enjoys the active, celebratory life that started all those years ago on a Mississippi college campus when she met a young Medgar Evers. They had an unusual, sometimes difficult relationship, but their love for each other and commitment to defeating racism were genuine. In telling their story, Reid has presented a most readable book about two national heroes involved in the worst and the best of the Civil Rights Movement.”

Medgar & Myrlie: Medgar Evers and the Love Story that Awakened America by Joy-Ann Reid (Mariner Books). Reviewed by Paul D. Pearlstein. “Now 90, Myrlie still enjoys the active, celebratory life that started all those years ago on a Mississippi college campus when she met a young Medgar Evers. They had an unusual, sometimes difficult relationship, but their love for each other and commitment to defeating racism were genuine. In telling their story, Reid has presented a most readable book about two national heroes involved in the worst and the best of the Civil Rights Movement.”

The Killing Ground: A Biography of Thermopylae by Myke Cole and Michael Livingston (Osprey Publishing). Reviewed by Peggy Kurkowski. “Each ‘Battle of Thermopylae’ represented varies in length and detail based on the availability of extant sources. Cole and Livingston admit — readily and repeatedly — where the historical record is silent on events and how they unfolded. In these instances, they doggedly pursue ‘the glimmer in the darkness of our lack of sources,’ but the reader may grow frustrated at the increasingly fragmentary nature of the oldest battle narratives (although it’s no fault of the authors).”

The Killing Ground: A Biography of Thermopylae by Myke Cole and Michael Livingston (Osprey Publishing). Reviewed by Peggy Kurkowski. “Each ‘Battle of Thermopylae’ represented varies in length and detail based on the availability of extant sources. Cole and Livingston admit — readily and repeatedly — where the historical record is silent on events and how they unfolded. In these instances, they doggedly pursue ‘the glimmer in the darkness of our lack of sources,’ but the reader may grow frustrated at the increasingly fragmentary nature of the oldest battle narratives (although it’s no fault of the authors).”

The Bullet Swallower: A Novel by Elizabeth Gonzalez James (Simon & Schuster). Reviewed by Bárbara Mujica. “Although the novel reads like a western with elements of magical realism, it is actually an exploration of complex metaphysical themes — among them, the nature of time. Does time really advance chronologically, or does humanity live and relive the same moment over and over? Are we caught in an endless spiral of violence and repentance? Is redemption actually possible? In The Bullet Swallower, Elizabeth Gonzalez James offers readers an intriguing and multifaceted story that will keep you thinking long after you turn the last page.”

The Bullet Swallower: A Novel by Elizabeth Gonzalez James (Simon & Schuster). Reviewed by Bárbara Mujica. “Although the novel reads like a western with elements of magical realism, it is actually an exploration of complex metaphysical themes — among them, the nature of time. Does time really advance chronologically, or does humanity live and relive the same moment over and over? Are we caught in an endless spiral of violence and repentance? Is redemption actually possible? In The Bullet Swallower, Elizabeth Gonzalez James offers readers an intriguing and multifaceted story that will keep you thinking long after you turn the last page.”

Relinquished: The Politics of Adoption and the Privilege of American Motherhood by Gretchen Sisson (St. Martin’s Press). Reviewed by Alice Stephens. “Infertile? Same-sex couple? Evangelical Christian? Zero-population-growth proponent? Too often, the “simple” solution if you fall into one of these categories but want a child is: You can always adopt. But where, exactly, do those babies come from? Typically, they are not, as the popular myth would have it, orphans. They have living mothers and fathers.”

Relinquished: The Politics of Adoption and the Privilege of American Motherhood by Gretchen Sisson (St. Martin’s Press). Reviewed by Alice Stephens. “Infertile? Same-sex couple? Evangelical Christian? Zero-population-growth proponent? Too often, the “simple” solution if you fall into one of these categories but want a child is: You can always adopt. But where, exactly, do those babies come from? Typically, they are not, as the popular myth would have it, orphans. They have living mothers and fathers.”

Trondheim: A Novel by Cormac James (Bellevue Literary Press). Reviewed by Marcie Geffner. “The setting and circumstances may seem ordinary, but there’s much more going on here than a mundane — if dreadfully awful — medical emergency. That opening-sentence suggestion aside, will Pierre, in fact, emerge from his coma? And will Lil and Alba’s marriage survive whatever comes? Trondheim allows readers to make the prognosis. Whatever it might be, James’ elegant novel will leave them shattered and uplifted.”

Trondheim: A Novel by Cormac James (Bellevue Literary Press). Reviewed by Marcie Geffner. “The setting and circumstances may seem ordinary, but there’s much more going on here than a mundane — if dreadfully awful — medical emergency. That opening-sentence suggestion aside, will Pierre, in fact, emerge from his coma? And will Lil and Alba’s marriage survive whatever comes? Trondheim allows readers to make the prognosis. Whatever it might be, James’ elegant novel will leave them shattered and uplifted.”

Dreaming of Ramadi in Detroit: Essays by Aisha Sabatini Sloan (Graywolf Press). Reviewed by Yelizaveta P. Renfro. “The 13 essays in Dreaming of Ramadi in Detroit deftly approach an array of topics, each building in collage-like fashion a revelatory, often startling reflection around a central subject or theme that pulls personal experience, research, and sharp observation into a vortex that ultimately holds together and gives us a way of seeing — if but for an instant — the shimmering complexity and interconnectedness of the world.”

Dreaming of Ramadi in Detroit: Essays by Aisha Sabatini Sloan (Graywolf Press). Reviewed by Yelizaveta P. Renfro. “The 13 essays in Dreaming of Ramadi in Detroit deftly approach an array of topics, each building in collage-like fashion a revelatory, often startling reflection around a central subject or theme that pulls personal experience, research, and sharp observation into a vortex that ultimately holds together and gives us a way of seeing — if but for an instant — the shimmering complexity and interconnectedness of the world.”

Fifty Beasts to Break Your Heart: And Other Stories by GennaRose Nethercott (Vintage). Reviewed by Tara Laskowski. “This is a literary assemblage, but it crosses into other genres, including fantasy, horror, and magical realism. It’s sure to delight readers who enjoy tales that don’t necessarily wrap up neatly but rather unspool, trailing into shadowed corners full of possibility. The kind that leave us either full of wonder or heavy with the weight of our own flaws. Nethercott seems to be telling us over and over that no matter how much magic we conjure, we can’t escape the mistakes that make us human or the obsessions that make us weak. But she unveils, too, the beauty in those flaws, and the sheer luck it is to be alive.”

Fifty Beasts to Break Your Heart: And Other Stories by GennaRose Nethercott (Vintage). Reviewed by Tara Laskowski. “This is a literary assemblage, but it crosses into other genres, including fantasy, horror, and magical realism. It’s sure to delight readers who enjoy tales that don’t necessarily wrap up neatly but rather unspool, trailing into shadowed corners full of possibility. The kind that leave us either full of wonder or heavy with the weight of our own flaws. Nethercott seems to be telling us over and over that no matter how much magic we conjure, we can’t escape the mistakes that make us human or the obsessions that make us weak. But she unveils, too, the beauty in those flaws, and the sheer luck it is to be alive.”

It’s Hard for Me to Live with Me: A Memoir by Rex Chapman with Seth Davis (Simon & Schuster). Reviewed by Gretchen Lida. “Despite being an avid reader of memoirs, I’m not exactly Chapman’s target audience. I have never watched an entire basketball game, and I’m leery of celebrity memoirs in general, as they often read like glossy, Oscar-worthy speeches and either avoid or ignore the blemishes and human flaws that make the genre worth reading. Yet there’s just one word to describe Chapman’s effort: Riveting.”

It’s Hard for Me to Live with Me: A Memoir by Rex Chapman with Seth Davis (Simon & Schuster). Reviewed by Gretchen Lida. “Despite being an avid reader of memoirs, I’m not exactly Chapman’s target audience. I have never watched an entire basketball game, and I’m leery of celebrity memoirs in general, as they often read like glossy, Oscar-worthy speeches and either avoid or ignore the blemishes and human flaws that make the genre worth reading. Yet there’s just one word to describe Chapman’s effort: Riveting.”

The Fox Wife: A Novel by Yangsze Choo (Henry Holt & Company). Reviewed by Bob Duffy. “Yangsze Choo’s The Fox Wife is a graceful, unassuming novel set in 1908 China in the waning years of that nation’s final imperial dynasty. The story is built around interlocking halves unspooling in alternating chapters, equal parts folktale and mystery. At first, the interlacing in this hybrid saga might seem discordant, its mildly fuzzy folkloric ambiguity at odds with the stark exigencies of investigation and discovery. But here, owing mostly to Choo’s remarkably understated narrative voice, the parallel plots mesh in pleasing yin-yang harmony.”

The Fox Wife: A Novel by Yangsze Choo (Henry Holt & Company). Reviewed by Bob Duffy. “Yangsze Choo’s The Fox Wife is a graceful, unassuming novel set in 1908 China in the waning years of that nation’s final imperial dynasty. The story is built around interlocking halves unspooling in alternating chapters, equal parts folktale and mystery. At first, the interlacing in this hybrid saga might seem discordant, its mildly fuzzy folkloric ambiguity at odds with the stark exigencies of investigation and discovery. But here, owing mostly to Choo’s remarkably understated narrative voice, the parallel plots mesh in pleasing yin-yang harmony.”

Vagabonds: Life on the Streets of Nineteenth-Century London by Oskar Jensen (The Experiment). Reviewed by Peggy Kurkowski. “Eschewing the predominant perspective of London’s street life made famous by its great chroniclers Charles Dickens and Henry Mayhew, Jensen chooses to look not at his subjects but rather with them as they make their homes and livelihoods in the streets. For these people, the streets aren’t merely paths from one place to another — they are places to be in and of themselves. Accessing new physical sources and those gleaned from digital archives, Jensen assembles long-forgotten voices from unread memoirs, obscure trial proceedings, periodicals, and reports to reveal individual worlds of ‘tenderness, horror, shame, and triumph.’”

Vagabonds: Life on the Streets of Nineteenth-Century London by Oskar Jensen (The Experiment). Reviewed by Peggy Kurkowski. “Eschewing the predominant perspective of London’s street life made famous by its great chroniclers Charles Dickens and Henry Mayhew, Jensen chooses to look not at his subjects but rather with them as they make their homes and livelihoods in the streets. For these people, the streets aren’t merely paths from one place to another — they are places to be in and of themselves. Accessing new physical sources and those gleaned from digital archives, Jensen assembles long-forgotten voices from unread memoirs, obscure trial proceedings, periodicals, and reports to reveal individual worlds of ‘tenderness, horror, shame, and triumph.’”

An Unfinished Love Story: A Personal History of the 1960s by Doris Kearns Goodwin (Simon & Schuster). Reviewed by Kitty Kelley. “The couple’s clash of political loyalties continued ‘provoking tension,’ as Goodwin insisted that civil rights, medical care for the aged, federal aid for education, and an overhaul of immigration only became law under President Johnson, while Richard countered that President Kennedy’s leadership set the tone and spirit of the decade. ‘Both of us looked back upon these years with a decided bias,’ she writes. ‘And our biases were not in harmony.’”

An Unfinished Love Story: A Personal History of the 1960s by Doris Kearns Goodwin (Simon & Schuster). Reviewed by Kitty Kelley. “The couple’s clash of political loyalties continued ‘provoking tension,’ as Goodwin insisted that civil rights, medical care for the aged, federal aid for education, and an overhaul of immigration only became law under President Johnson, while Richard countered that President Kennedy’s leadership set the tone and spirit of the decade. ‘Both of us looked back upon these years with a decided bias,’ she writes. ‘And our biases were not in harmony.’”

The Mars House: A Novel by Natasha Pulley (Bloomsbury Publishing). Reviewed by Mariko Hewer. “With the ever-increasing worry about climate change and its devastating effects, it can be difficult to read a book whose premise relies on our planet becoming uninhabitable. Although it concerns exactly that, Natasha Pulley’s queer sci-fi romance, The Mars House, nevertheless offers hope for the future of mankind, even if that future takes place on another planet.”

The Mars House: A Novel by Natasha Pulley (Bloomsbury Publishing). Reviewed by Mariko Hewer. “With the ever-increasing worry about climate change and its devastating effects, it can be difficult to read a book whose premise relies on our planet becoming uninhabitable. Although it concerns exactly that, Natasha Pulley’s queer sci-fi romance, The Mars House, nevertheless offers hope for the future of mankind, even if that future takes place on another planet.”

Revolusi: Indonesia and the Birth of the Modern World by David Van Reybrouck (W.W. Norton & Company). Reviewed by Todd Kushner. “In Revolusi, Belgian cultural historian David Van Reybrouck tells the captivating story of Dutch colonization of the East Indies and Indonesians’ fight for freedom. Given the 300-year span of the Dutch colonial period, Van Reybrouck had to limit his coverage to the most important developments. The key feature of the book, however, is Van Reybrouck’s punctuating his analysis of the 1930-1950 period with first-person narratives of those who lived through it.”

Revolusi: Indonesia and the Birth of the Modern World by David Van Reybrouck (W.W. Norton & Company). Reviewed by Todd Kushner. “In Revolusi, Belgian cultural historian David Van Reybrouck tells the captivating story of Dutch colonization of the East Indies and Indonesians’ fight for freedom. Given the 300-year span of the Dutch colonial period, Van Reybrouck had to limit his coverage to the most important developments. The key feature of the book, however, is Van Reybrouck’s punctuating his analysis of the 1930-1950 period with first-person narratives of those who lived through it.”

The Translator’s Daughter: A Memoir by Grace Loh Prasad (Mad Creek Books). Reviewed by Priyanka Champaneri. “The immigrant experience is sometimes touted as a blessing in an increasingly globalized world where being a cultural chameleon is the new currency. To speak multiple languages, to be at home in multiple places, is to be a citizen of the world. Loh Prasad, however, tells the story of how it was and is for her, a story that reflects the voices of those who are not so much confidently straddling cultures as stuck in the fissure between them, grasping for the lost hands that once held theirs.”

The Translator’s Daughter: A Memoir by Grace Loh Prasad (Mad Creek Books). Reviewed by Priyanka Champaneri. “The immigrant experience is sometimes touted as a blessing in an increasingly globalized world where being a cultural chameleon is the new currency. To speak multiple languages, to be at home in multiple places, is to be a citizen of the world. Loh Prasad, however, tells the story of how it was and is for her, a story that reflects the voices of those who are not so much confidently straddling cultures as stuck in the fissure between them, grasping for the lost hands that once held theirs.”

Bomb Island: A Novel by Stephen Hundley (Hub City Press). Reviewed by Willem Marx. “Near a submerged nuclear bomb in Georgia sits an island nature reserve full of horses as paranoid as the humans ought to be. A tiger named Sugar hunts the resident ponies from a jungled interior, where members of a failed commune secretly live. Though the commune’s leader brought Sugar to the place years ago, not everyone is happy about living with a full-grown predator anymore. This is the setting of Stephen Hundley’s visionary debut novel, Bomb Island. It’s a real place…sort of.”

Bomb Island: A Novel by Stephen Hundley (Hub City Press). Reviewed by Willem Marx. “Near a submerged nuclear bomb in Georgia sits an island nature reserve full of horses as paranoid as the humans ought to be. A tiger named Sugar hunts the resident ponies from a jungled interior, where members of a failed commune secretly live. Though the commune’s leader brought Sugar to the place years ago, not everyone is happy about living with a full-grown predator anymore. This is the setting of Stephen Hundley’s visionary debut novel, Bomb Island. It’s a real place…sort of.”

James: A Novel by Percival Everett (Doubleday). Reviewed by Nick Havey. “My last memory of Mark Twain’s The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn is that it sparked a debate in my sophomore-year English class over whether or not white people could say the N-word. My teacher, bless her heart, wanted to encourage the discussion but did not feel comfortable saying the word herself. That did not, of course, stop the teenage Arizona white boys from throwing the horrific epithet around without a care in the world. I am thankful that Percival Everett has now provided a new memory in the form of James. The book is, in a word, electrifying.”

James: A Novel by Percival Everett (Doubleday). Reviewed by Nick Havey. “My last memory of Mark Twain’s The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn is that it sparked a debate in my sophomore-year English class over whether or not white people could say the N-word. My teacher, bless her heart, wanted to encourage the discussion but did not feel comfortable saying the word herself. That did not, of course, stop the teenage Arizona white boys from throwing the horrific epithet around without a care in the world. I am thankful that Percival Everett has now provided a new memory in the form of James. The book is, in a word, electrifying.”

Belly Woman: Birth, Blood & Ebola: The Untold Story by Benjamin Black (Neem Tree Press). Reviewed by Jay Hancock. “Doctors delivering babies, especially those performing emergency cesarean sections, have a very hard time doing this. A physician in the Ebola clinic told Black, ‘I would feel safer here’ than in the maternity hospital. Black is doubly brave — risking death to help people and then writing this heartbreakingly honest book. When it was all over, as Britain’s government handed out medals to Ebola heroes, a researcher asked him to summarize his feelings. ‘Ashamed,’ he said.”

Belly Woman: Birth, Blood & Ebola: The Untold Story by Benjamin Black (Neem Tree Press). Reviewed by Jay Hancock. “Doctors delivering babies, especially those performing emergency cesarean sections, have a very hard time doing this. A physician in the Ebola clinic told Black, ‘I would feel safer here’ than in the maternity hospital. Black is doubly brave — risking death to help people and then writing this heartbreakingly honest book. When it was all over, as Britain’s government handed out medals to Ebola heroes, a researcher asked him to summarize his feelings. ‘Ashamed,’ he said.”

Bare Knuckle: Bobby Gunn, 73-0 Undefeated. A Dad. A Dream. A Fight Like You’ve Never Seen. by Stayton Bonner (Blackstone Publishing). Reviewed by Lawrence De Maria. “It’s hard not to root for Gunn, even in his regular gloved fights with professional boxers, who occasionally cleaned his clock. But in an era when we put a lot of lipstick on a lot of pigs, Gunn still stands out…It’s a compelling, sad, hopeful, and sobering story all at once, and one with photographs, chapter notes, a bibliography, and an index worthy of a WWII biography. Bare Knuckle is an excellent, serious book. In it, Stayton Bonner has given us a history we may not like but should know.”

Bare Knuckle: Bobby Gunn, 73-0 Undefeated. A Dad. A Dream. A Fight Like You’ve Never Seen. by Stayton Bonner (Blackstone Publishing). Reviewed by Lawrence De Maria. “It’s hard not to root for Gunn, even in his regular gloved fights with professional boxers, who occasionally cleaned his clock. But in an era when we put a lot of lipstick on a lot of pigs, Gunn still stands out…It’s a compelling, sad, hopeful, and sobering story all at once, and one with photographs, chapter notes, a bibliography, and an index worthy of a WWII biography. Bare Knuckle is an excellent, serious book. In it, Stayton Bonner has given us a history we may not like but should know.”

Orwell’s Ghosts: Wisdom and Warnings for the Twenty-First Century by Laura Beers (W.W. Norton & Company). Reviewed by John P. Loonam. “Even in our current partisan divide, it seems both left and right can agree on one principle of political discourse: The other side’s policies aren’t just bad, they’re downright Orwellian. Whether it’s right-wing hysteria about tech companies banning free speech or the left’s complaint that MAGA Republicans are rewriting the history of January 6th, both sides cite Orwell as their inspiration. Daniel Patrick Moynihan told us we’re entitled to our own opinions — and despite his warning, increasingly to our own facts — but are we really entitled to our own Orwell, too?”

Orwell’s Ghosts: Wisdom and Warnings for the Twenty-First Century by Laura Beers (W.W. Norton & Company). Reviewed by John P. Loonam. “Even in our current partisan divide, it seems both left and right can agree on one principle of political discourse: The other side’s policies aren’t just bad, they’re downright Orwellian. Whether it’s right-wing hysteria about tech companies banning free speech or the left’s complaint that MAGA Republicans are rewriting the history of January 6th, both sides cite Orwell as their inspiration. Daniel Patrick Moynihan told us we’re entitled to our own opinions — and despite his warning, increasingly to our own facts — but are we really entitled to our own Orwell, too?”

Starry Field: A Memoir of Lost History by Margaret Juhae Lee (Melville House). Reviewed by Alice Stephens. “A gallery of photos and documents richly illustrates the scope of the historical setting of the memoir. The narrative threads back and forth in time (with some fanciful embroidering of events), stitching a vivid account of a country, a family, and individuals grappling with the past in order to make sense of the future. While many in power in Korea today would rather leave the past unexcavated, Margaret Juhae Lee demonstrates that looking back can be a way to move forward.”

Starry Field: A Memoir of Lost History by Margaret Juhae Lee (Melville House). Reviewed by Alice Stephens. “A gallery of photos and documents richly illustrates the scope of the historical setting of the memoir. The narrative threads back and forth in time (with some fanciful embroidering of events), stitching a vivid account of a country, a family, and individuals grappling with the past in order to make sense of the future. While many in power in Korea today would rather leave the past unexcavated, Margaret Juhae Lee demonstrates that looking back can be a way to move forward.”

In the Service of the Shogun: The Real Story of William Adams by Frederik Cryns (Reaktion Books). Reviewed by Peggy Kurkowski. “One of the surprising bits of Cryns’ biography describes the ‘Jesuit slander’ against Adams. For whatever reason — but most likely because he was a Protestant and aligned with the Dutch — Jesuit missionaries in Japan at the time continually painted him and his men as ‘pirates’ who should be executed. But Ieyasu’s keen interrogation of Adams and the imperial machinations of Spain only ‘deepened his mistrust of the Jesuits,’ who soon found themselves on the wrong side of the shogun.”

In the Service of the Shogun: The Real Story of William Adams by Frederik Cryns (Reaktion Books). Reviewed by Peggy Kurkowski. “One of the surprising bits of Cryns’ biography describes the ‘Jesuit slander’ against Adams. For whatever reason — but most likely because he was a Protestant and aligned with the Dutch — Jesuit missionaries in Japan at the time continually painted him and his men as ‘pirates’ who should be executed. But Ieyasu’s keen interrogation of Adams and the imperial machinations of Spain only ‘deepened his mistrust of the Jesuits,’ who soon found themselves on the wrong side of the shogun.”

Bury Your Gays by Chuck Tingle (Tor Nightfire). Reviewed by Nick Havey. “Meet Misha Byrne. He’s basically a young, queer Wes Craven at the midpoint of an already trailblazing career in Tinseltown. He’s got a solid back catalog of films, and his ‘X-Files meets Doctor Who’-style TV show is headed for its biggest and baddest season finale yet. The only problem? The studio bigwigs aren’t exactly happy with the girl-on-girl romance he’s written into it. He’s promptly instructed by his bosses to ‘bury your gays,’ wordplay that does double duty as an imperative to kill his queer characters and tone down just how inclusive the work is.”

Bury Your Gays by Chuck Tingle (Tor Nightfire). Reviewed by Nick Havey. “Meet Misha Byrne. He’s basically a young, queer Wes Craven at the midpoint of an already trailblazing career in Tinseltown. He’s got a solid back catalog of films, and his ‘X-Files meets Doctor Who’-style TV show is headed for its biggest and baddest season finale yet. The only problem? The studio bigwigs aren’t exactly happy with the girl-on-girl romance he’s written into it. He’s promptly instructed by his bosses to ‘bury your gays,’ wordplay that does double duty as an imperative to kill his queer characters and tone down just how inclusive the work is.”

Vicious and Immoral: Homosexuality, the American Revolution, and the Trials of Robert Newburgh by John Gilbert McCurdy (Johns Hopkins University Press). Reviewed by James A. Percoco. “Throughout the book, McCurdy, both a scholar of early American and LGBTQ+ history and a gay man, examines the issue of homosexuality within the larger tale of the war that birthed the United States. His prose is lucid, accessible, and compelling as he relates to readers the series of indignities endured by Captain Newburgh. Ultimately, it’s a history, biography, courtroom drama, and exploration of life among the Redcoats all rolled into one.”

Vicious and Immoral: Homosexuality, the American Revolution, and the Trials of Robert Newburgh by John Gilbert McCurdy (Johns Hopkins University Press). Reviewed by James A. Percoco. “Throughout the book, McCurdy, both a scholar of early American and LGBTQ+ history and a gay man, examines the issue of homosexuality within the larger tale of the war that birthed the United States. His prose is lucid, accessible, and compelling as he relates to readers the series of indignities endured by Captain Newburgh. Ultimately, it’s a history, biography, courtroom drama, and exploration of life among the Redcoats all rolled into one.”

Escape from Shadow Physics: The Quest to End the Dark Ages of Quantum Theory by Adam Forrest Kay (Basic Books). Reviewed by Stephen Case. “Taking Einstein’s side, Kay devotes much of Escape from Shadow Physics to challenging the very notion of completeness. An uncowed disbeliever, he declares his ‘book is about dissent…damn the torpedoes, full speed ahead!’ With dual doctorates from Oxbridge, the author has the credibility to do just that. Permeating this agreeably readable work are his boundless curiosity, mastery of physics, and command of science history (the short bios of famous scientists peppering the text reveal this broad grasp).”

Escape from Shadow Physics: The Quest to End the Dark Ages of Quantum Theory by Adam Forrest Kay (Basic Books). Reviewed by Stephen Case. “Taking Einstein’s side, Kay devotes much of Escape from Shadow Physics to challenging the very notion of completeness. An uncowed disbeliever, he declares his ‘book is about dissent…damn the torpedoes, full speed ahead!’ With dual doctorates from Oxbridge, the author has the credibility to do just that. Permeating this agreeably readable work are his boundless curiosity, mastery of physics, and command of science history (the short bios of famous scientists peppering the text reveal this broad grasp).”

Nicked by M.T. Anderson (Pantheon). Reviewed by Marcie Geffner. “Despite its overtly spiritual subject matter, M.T. Anderson’s Nicked isn’t a story about religion. Rather, it’s a fluffy, irreverent, and often hilarious mashup of a heist, a quest, and…wait for it…a rom-com. The novel’s philosophy might best be described as ‘seize the day’ — and if you can corrupt an innocent young monk while you’re at it, all the better.”

Nicked by M.T. Anderson (Pantheon). Reviewed by Marcie Geffner. “Despite its overtly spiritual subject matter, M.T. Anderson’s Nicked isn’t a story about religion. Rather, it’s a fluffy, irreverent, and often hilarious mashup of a heist, a quest, and…wait for it…a rom-com. The novel’s philosophy might best be described as ‘seize the day’ — and if you can corrupt an innocent young monk while you’re at it, all the better.”

A Question of Belonging: Crónicas by Hebe Uhart; translated by Anna Vilner (Archipelago Books). Reviewed by Karl Straub. “We often associate truth with a clinical tone, but Uhart had no patience for such orthodoxy. Her crónicas were long on style but packed with serious reporting and empathy. She socialized, investigated, and listened, drawing whatever she could from the people she met. She dug out their perceptions and perspectives and then gave us the fruits of her research in the voice of a master scribe.”

A Question of Belonging: Crónicas by Hebe Uhart; translated by Anna Vilner (Archipelago Books). Reviewed by Karl Straub. “We often associate truth with a clinical tone, but Uhart had no patience for such orthodoxy. Her crónicas were long on style but packed with serious reporting and empathy. She socialized, investigated, and listened, drawing whatever she could from the people she met. She dug out their perceptions and perspectives and then gave us the fruits of her research in the voice of a master scribe.”

Willie, Waylon, and the Boys: How Nashville Outsiders Changed Country Music Forever by Brian Fairbanks (Hachette Books). Reviewed by Michael Causey. “Music books like this one are a funny subspecies because the author’s personality factors heavily in the reading experience. In other words, you could read an outstanding history of, say, World War II and not necessarily want to hang with its author. But for a book about musicians — especially beloved ones like Willie Nelson and Waylon Jennings — to be great, it’s kind of important to be able to imagine having a beer with the author and talking tunes. I’d be psyched to hoist a few beers with Brian Fairbanks anytime.”

Willie, Waylon, and the Boys: How Nashville Outsiders Changed Country Music Forever by Brian Fairbanks (Hachette Books). Reviewed by Michael Causey. “Music books like this one are a funny subspecies because the author’s personality factors heavily in the reading experience. In other words, you could read an outstanding history of, say, World War II and not necessarily want to hang with its author. But for a book about musicians — especially beloved ones like Willie Nelson and Waylon Jennings — to be great, it’s kind of important to be able to imagine having a beer with the author and talking tunes. I’d be psyched to hoist a few beers with Brian Fairbanks anytime.”

There Are Rivers in the Sky by Elif Shafak (Knopf). Reviewed by Martha Anne Toll. “Zaleekah’s is a family of immigrants to England, albeit well-educated and cosmopolitan ones. She has fallen in love with a woman, and her journey takes her back to her roots, where she must delve into the meaning of her family’s past. As she moves to embrace her lifestyle and share it with her relatives, readers are exposed to the nuances of generational and cultural differences surrounding sexual identity.”

There Are Rivers in the Sky by Elif Shafak (Knopf). Reviewed by Martha Anne Toll. “Zaleekah’s is a family of immigrants to England, albeit well-educated and cosmopolitan ones. She has fallen in love with a woman, and her journey takes her back to her roots, where she must delve into the meaning of her family’s past. As she moves to embrace her lifestyle and share it with her relatives, readers are exposed to the nuances of generational and cultural differences surrounding sexual identity.”

We’re Alone: Essays by Edwidge Danticat (Graywolf Press). Reviewed by Jennifer Bort Yacovissi. “Given the historical abuse, pillage, and general catastrophe inflicted by outsiders on Danticat’s home country — and onto members of its diaspora — it is this final interpretation that feels most apt. Danticat speaks here as though chatting with friends: warm, accessible, but also vibrating with a controlled rage that doesn’t need to be fully articulated because friends understand and share it. A compelling storyteller, Danticat weaves multiple threads through her essays of family, of separation and reunion, of Haitian culture and history, of writers and writing, and of calamities past, present, and yet to come.”

We’re Alone: Essays by Edwidge Danticat (Graywolf Press). Reviewed by Jennifer Bort Yacovissi. “Given the historical abuse, pillage, and general catastrophe inflicted by outsiders on Danticat’s home country — and onto members of its diaspora — it is this final interpretation that feels most apt. Danticat speaks here as though chatting with friends: warm, accessible, but also vibrating with a controlled rage that doesn’t need to be fully articulated because friends understand and share it. A compelling storyteller, Danticat weaves multiple threads through her essays of family, of separation and reunion, of Haitian culture and history, of writers and writing, and of calamities past, present, and yet to come.”

That Librarian: The Fight Against Book Banning in America by Amanda Jones (Bloomsbury Publishing). Reviewed by Sarah Trembath. “Amanda Jones is a badass. She’s not on stage in front of tens of thousands of screaming fans like Beyoncé. She didn’t eliminate the national debt. I don’t think she jumps out of planes. Still, she’s a badass, but not just because the teenage friends of her teenage daughter said, ‘Your mom is a badass,’ which is a major life accomplishment, as anyone with teens knows. Amanda Jones is a badass because she’s holding down the fort while the fort is under attack.”

That Librarian: The Fight Against Book Banning in America by Amanda Jones (Bloomsbury Publishing). Reviewed by Sarah Trembath. “Amanda Jones is a badass. She’s not on stage in front of tens of thousands of screaming fans like Beyoncé. She didn’t eliminate the national debt. I don’t think she jumps out of planes. Still, she’s a badass, but not just because the teenage friends of her teenage daughter said, ‘Your mom is a badass,’ which is a major life accomplishment, as anyone with teens knows. Amanda Jones is a badass because she’s holding down the fort while the fort is under attack.”

Pentimento Mori by Valeria Corciolani (Kazabo Publishing). Reviewed by Drew Gallagher. “My Italian is a bit rusty, but I believe the loose translation of the title of Valeria Corciolani’s Pentimento Mori is ‘catnip for art-history majors.’ At least, it should be. This entertaining romp accompanies art historian Edna Silvera through the Italian countryside as she tries to solve a murder and unearth the provenance of a mysterious painting found in the victim’s shop. Priority-wise, the killing doesn’t necessarily come first for her.”

Pentimento Mori by Valeria Corciolani (Kazabo Publishing). Reviewed by Drew Gallagher. “My Italian is a bit rusty, but I believe the loose translation of the title of Valeria Corciolani’s Pentimento Mori is ‘catnip for art-history majors.’ At least, it should be. This entertaining romp accompanies art historian Edna Silvera through the Italian countryside as she tries to solve a murder and unearth the provenance of a mysterious painting found in the victim’s shop. Priority-wise, the killing doesn’t necessarily come first for her.”

John Lewis: A Life by David Greenberg (Simon & Schuster). Reviewed by Kitty Kelley. “A masterful biography is like a shooting star. It’s a celestial phenomenon that lights up the night sky and bestows a sense of wonder and excitement. Such a sensation occurs when the stars align and match a subject of worth with an estimable writer. That kind of luminous pairing occurs in David Greenberg’s John Lewis: A Life, the first major biography of the man Martin Luther King Jr. called ‘the boy from Troy.’”

John Lewis: A Life by David Greenberg (Simon & Schuster). Reviewed by Kitty Kelley. “A masterful biography is like a shooting star. It’s a celestial phenomenon that lights up the night sky and bestows a sense of wonder and excitement. Such a sensation occurs when the stars align and match a subject of worth with an estimable writer. That kind of luminous pairing occurs in David Greenberg’s John Lewis: A Life, the first major biography of the man Martin Luther King Jr. called ‘the boy from Troy.’”

Blind Spots: When Medicine Gets It Wrong, and What It Means for Our Health by Marty Makary (Bloomsbury Publishing). Reviewed by Randy Cepuch. “While much of Blind Spots encourages skepticism, anti-vaxxers who insist that some of those who’ve taken the Hippocratic Oath are hypocrites regarding covid will find little support here. Instead, they’ll find the story of how, more than 200 years ago, a doctor demonstrated that exposure to cowpox led to immunity from smallpox — the dawning of vaccines — and how Thomas Jefferson created the National Vaccine Institute to begin the ultimately successful eradication of the disfiguring illness.”

Blind Spots: When Medicine Gets It Wrong, and What It Means for Our Health by Marty Makary (Bloomsbury Publishing). Reviewed by Randy Cepuch. “While much of Blind Spots encourages skepticism, anti-vaxxers who insist that some of those who’ve taken the Hippocratic Oath are hypocrites regarding covid will find little support here. Instead, they’ll find the story of how, more than 200 years ago, a doctor demonstrated that exposure to cowpox led to immunity from smallpox — the dawning of vaccines — and how Thomas Jefferson created the National Vaccine Institute to begin the ultimately successful eradication of the disfiguring illness.”

Innie Shadows by Olivia M. Coetzee (House of Anansi Press). Reviewed by Susi Wyss. “In the first chapter of Olivia M. Coetzee’s debut novel, Innie Shadows, the burned body of a man in his early 20s has been found on a rugby field outside of Cape Town, South Africa. Ley, a newly promoted detective, has been assigned to the case, with no immediate clues as to the identity of the man or how he met his gruesome end. While this opening may sound like it follows the usual blueprint for a mystery novel, Coetzee’s tale is anything but formulaic.”

Innie Shadows by Olivia M. Coetzee (House of Anansi Press). Reviewed by Susi Wyss. “In the first chapter of Olivia M. Coetzee’s debut novel, Innie Shadows, the burned body of a man in his early 20s has been found on a rugby field outside of Cape Town, South Africa. Ley, a newly promoted detective, has been assigned to the case, with no immediate clues as to the identity of the man or how he met his gruesome end. While this opening may sound like it follows the usual blueprint for a mystery novel, Coetzee’s tale is anything but formulaic.”

Firebrands: The Untold Story of Four Women Who Made and Unmade Prohibition by Gioia Diliberto (University of Chicago Press). Reviewed by Rose Rankin. “In 1920, when the narrative begins, Ella Boole, president of the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union, had just achieved her dream of getting alcohol outlawed nationwide, but as this stereotypical scold of a woman understood, passing a law and enforcing it are two very different things. So, the male leadership in the Executive Branch of the U.S. Government gave the most unenviable job in the country to a female: lawyer Mabel Walker Willebrandt, who became assistant attorney general in 1921.”

Firebrands: The Untold Story of Four Women Who Made and Unmade Prohibition by Gioia Diliberto (University of Chicago Press). Reviewed by Rose Rankin. “In 1920, when the narrative begins, Ella Boole, president of the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union, had just achieved her dream of getting alcohol outlawed nationwide, but as this stereotypical scold of a woman understood, passing a law and enforcing it are two very different things. So, the male leadership in the Executive Branch of the U.S. Government gave the most unenviable job in the country to a female: lawyer Mabel Walker Willebrandt, who became assistant attorney general in 1921.”

The Volcano Daughters: A Novel by Gina María Balibrera (Pantheon). Reviewed by Anne Eliot Feldman. “Spanning 1914 to 1942, the novel begins in Izalco, a village on a volcano in western El Salvador. The future ghosts are still alive, sisters Graciela and Consuelo (the book’s protagonists) are small, and everyone is growing up together. Their mothers all work on a coffee plantation and protect their daughters ‘with joyful ferocity.’ A shadowy assortment of largely absent fathers has no impact on their lives, except for Graciela and Consuelo’s father, Germán, whose boyhood best friend — a general referred to pejoratively as El Gran Pendejo — now rules the land.”

The Volcano Daughters: A Novel by Gina María Balibrera (Pantheon). Reviewed by Anne Eliot Feldman. “Spanning 1914 to 1942, the novel begins in Izalco, a village on a volcano in western El Salvador. The future ghosts are still alive, sisters Graciela and Consuelo (the book’s protagonists) are small, and everyone is growing up together. Their mothers all work on a coffee plantation and protect their daughters ‘with joyful ferocity.’ A shadowy assortment of largely absent fathers has no impact on their lives, except for Graciela and Consuelo’s father, Germán, whose boyhood best friend — a general referred to pejoratively as El Gran Pendejo — now rules the land.”

Sister Deborah by Scholastique Mukasonga; translated by Mark Polizzotti (Archipelago Books). Reviewed by Bárbara Mujica. “Father Marcus preached the coming of the Black messiah, but Sister Deborah clarified that it would be a woman. She would come on a cloud from which she would drop a seed, imbuto, that would produce a harvest so abundant that everyone would have enough to eat. Rwandan women, who had been toiling in the fields to cultivate beans, sweet potatoes, and cassava — foods originally from the Americas that require a great deal of work to grow — would no longer have to break their backs.”

Sister Deborah by Scholastique Mukasonga; translated by Mark Polizzotti (Archipelago Books). Reviewed by Bárbara Mujica. “Father Marcus preached the coming of the Black messiah, but Sister Deborah clarified that it would be a woman. She would come on a cloud from which she would drop a seed, imbuto, that would produce a harvest so abundant that everyone would have enough to eat. Rwandan women, who had been toiling in the fields to cultivate beans, sweet potatoes, and cassava — foods originally from the Americas that require a great deal of work to grow — would no longer have to break their backs.”

Ordinary Disasters: How I Stopped Being a Model Minority by Anne Anlin Cheng (Pantheon). Reviewed by Alice Stephens. “While the author recalls indignities inflicted upon her, doing little to hide identities of institutions and colleagues even if not naming them directly, this collection goes well beyond the personal as Cheng stitches her witness testimony into the broader tapestries of Asian American history and culture, the immigrant experience, and American womanhood. Often, all three are braided together, as in the essay ‘The Look,’ a six-part meditation on beauty, fashion, and what it means to be divided from your own body.”

Ordinary Disasters: How I Stopped Being a Model Minority by Anne Anlin Cheng (Pantheon). Reviewed by Alice Stephens. “While the author recalls indignities inflicted upon her, doing little to hide identities of institutions and colleagues even if not naming them directly, this collection goes well beyond the personal as Cheng stitches her witness testimony into the broader tapestries of Asian American history and culture, the immigrant experience, and American womanhood. Often, all three are braided together, as in the essay ‘The Look,’ a six-part meditation on beauty, fashion, and what it means to be divided from your own body.”

American Scary: A History of Horror, from Salem to Stephen King and Beyond by Jeremy Dauber (Algonquin Books). Reviewed by Michael Causey. “Want to see something uniquely terrifying? It’s simple. Just find the nearest mirror and take a deep look at the face staring back at you. No, this isn’t the beginning of a playground taunt. It’s more a cold, hard truth. You are the source of your own horror. ‘Show me what scares you, and I’ll show you your soul,’ writes Jeremy Dauber in his excellent, authoritative, and fascinating panorama of the horror genre in the U.S., American Scary.”

American Scary: A History of Horror, from Salem to Stephen King and Beyond by Jeremy Dauber (Algonquin Books). Reviewed by Michael Causey. “Want to see something uniquely terrifying? It’s simple. Just find the nearest mirror and take a deep look at the face staring back at you. No, this isn’t the beginning of a playground taunt. It’s more a cold, hard truth. You are the source of your own horror. ‘Show me what scares you, and I’ll show you your soul,’ writes Jeremy Dauber in his excellent, authoritative, and fascinating panorama of the horror genre in the U.S., American Scary.”

Valley So Low: One Lawyer’s Fight For Justice in the Wake of America’s Great Coal Catastrophe by Jared Sullivan (Knopf). Reviewed by Larry Matthews. “The dike holding back the ash wasn’t concrete, it was dirt. Not long after midnight on December 22nd, it gave way. More than a billion gallons of coal-ash slurry broke free, producing a wave 50 feet high. It filled the Emory, tossing fish 40 feet onto the riverbank. It crushed trees and smothered roads and everything else in its path, including homes. The toxic stew killed people and animals and ruined the landscape. Jared Sullivan’s Valley So Low tells the story of what happened next.”

Valley So Low: One Lawyer’s Fight For Justice in the Wake of America’s Great Coal Catastrophe by Jared Sullivan (Knopf). Reviewed by Larry Matthews. “The dike holding back the ash wasn’t concrete, it was dirt. Not long after midnight on December 22nd, it gave way. More than a billion gallons of coal-ash slurry broke free, producing a wave 50 feet high. It filled the Emory, tossing fish 40 feet onto the riverbank. It crushed trees and smothered roads and everything else in its path, including homes. The toxic stew killed people and animals and ruined the landscape. Jared Sullivan’s Valley So Low tells the story of what happened next.”

Four Points of the Compass: The Unexpected History of Direction by Jerry Brotton (Atlantic Monthly Press). Reviewed by Anne Cassidy. “Although the west is often associated with death because of its tie to the setting sun, it’s also connected with rebirth and new life. The west is a place of possibility, a realm of the imagination, home of Atlantis and other fantastical places. While, in the U.S., the west is linked with the frontier and Manifest Destiny, Henry David Thoreau equated it with wildness, which he saw as the ‘preservation of the world.’”

Four Points of the Compass: The Unexpected History of Direction by Jerry Brotton (Atlantic Monthly Press). Reviewed by Anne Cassidy. “Although the west is often associated with death because of its tie to the setting sun, it’s also connected with rebirth and new life. The west is a place of possibility, a realm of the imagination, home of Atlantis and other fantastical places. While, in the U.S., the west is linked with the frontier and Manifest Destiny, Henry David Thoreau equated it with wildness, which he saw as the ‘preservation of the world.’”

Taiwan Travelogue: A Novel by Yáng Shuāng-zǐ; translated by Lin King (Graywolf Press). Reviewed by Marcie Geffner. “Chizuru is much more than a language expert. Soon after the two women meet, she brings Chizuko an entire wardrobe of new clothing, a library card, local maps, and a list of area restaurants. In addition to her duties as an interpreter, she also acts as Chizuko’s personal assistant, travel agent, private chef, and procurer of large quantities of regional foods to meet Chizuko’s daily demands. What more could a traveling author desire? In Chizuko’s case, a lot.”

Taiwan Travelogue: A Novel by Yáng Shuāng-zǐ; translated by Lin King (Graywolf Press). Reviewed by Marcie Geffner. “Chizuru is much more than a language expert. Soon after the two women meet, she brings Chizuko an entire wardrobe of new clothing, a library card, local maps, and a list of area restaurants. In addition to her duties as an interpreter, she also acts as Chizuko’s personal assistant, travel agent, private chef, and procurer of large quantities of regional foods to meet Chizuko’s daily demands. What more could a traveling author desire? In Chizuko’s case, a lot.”

The Magnificent Ruins: A Novel by Nayantara Roy (Algonquin Books). Reviewed by Anne Eliot Feldman. “The Magnificent Ruins is beautifully written. Lila and Maya’s mother-daughter dynamic — revealing a mutual desire to be close and the impossibility of doing so — elicits the book’s most poignant passages. Roy, an award-winning short-story writer, playwright, and TV executive, fleshes out the narrative (and the origin of the Lahiris’ troubles) with vivid depictions of Bengali history and life in Kolkata, including the intrigue surrounding an approaching election that threatens the status quo.”

The Magnificent Ruins: A Novel by Nayantara Roy (Algonquin Books). Reviewed by Anne Eliot Feldman. “The Magnificent Ruins is beautifully written. Lila and Maya’s mother-daughter dynamic — revealing a mutual desire to be close and the impossibility of doing so — elicits the book’s most poignant passages. Roy, an award-winning short-story writer, playwright, and TV executive, fleshes out the narrative (and the origin of the Lahiris’ troubles) with vivid depictions of Bengali history and life in Kolkata, including the intrigue surrounding an approaching election that threatens the status quo.”

Love sincere, ultimately meaningless lists? Support the nonprofit Independent!