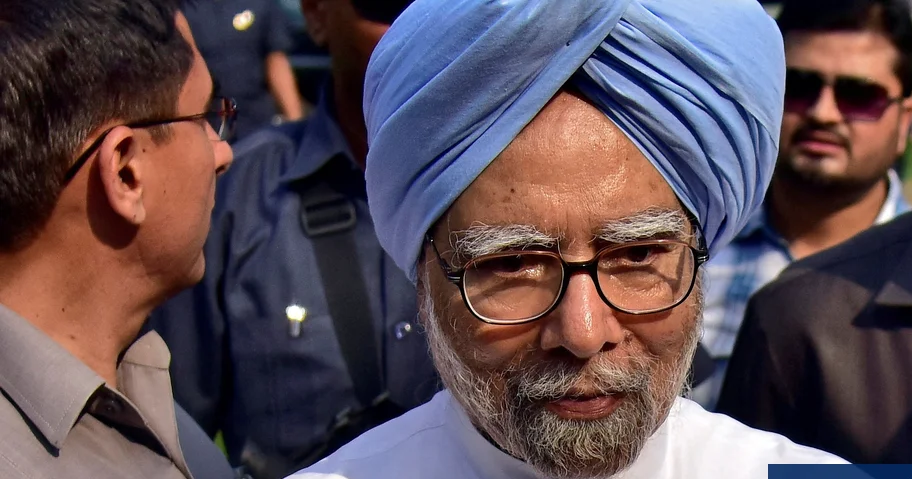

Manmohan Singh, India’s first Sikh prime minister and the architect of the big-bang economic reforms that set the stage for the country’s emergence as a global powerhouse, has died aged 92.

A hospital statement attributed Singh’s death to “age-related medical conditions”.

The government announced seven days of mourning along with a state funeral for Singh. The Indian prime minister, Narendra Modi, paid tribute to him, saying: “India mourns the loss of one of its most distinguished leaders.”

Singh, called India’s “reluctant prime minister” due to his shyness and preference for being behind the scenes, was considered an unlikely choice to lead the world’s biggest democracy. But when Congress leader Sonia Gandhi led her party to a surprise victory in 2004, she turned to Singh to be prime minister.

Famed for his trademark sky-blue turbans and home-spun white kurta pyjamas, Singh became the country’s first non-Hindu prime minister. He served a rare full two terms as prime minister in India’s tumultuous politics and is credited with spurring the rapid economic growth that lifted tens of millions of Indians from poverty.

Born in 1932 in Gah, a village in present-day Pakistan, Singh’s early life was shaped by hardship and he walked miles to go to school.

His family was uprooted during the partition of the subcontinent after independence from Britain in 1947 and migrated to the Sikh holy city of Amritsar in India.

Singh, one of 10 siblings, was so determined to get an education he would study at night under streetlights to escape the noise in his joint-family home. His brother, Surjit Singh, recalled his father “used to say Manmohan will be the prime minister of India” because he “always had his nose in a book”.

His diligence paid off when he won scholarships to study economics at Cambridge and later at Oxford, where he earned a doctorate.

He went on to hold pivotal government roles including serving as head of India’s central bank. Later, he worked for the International Monetary Fund.

Singh was pitchforked into politics in 1991 when India, facing one of the worst-ever economic crises, was on the brink of default. The then prime minister, PV Narasimha Rao, drafted Singh to be his finance minister.

In a seismic shift, Singh broke away from India’s Soviet-style economic planning model. He quoted Victor Hugo – “No power on earth can stop an idea whose time has come” – before adding that “the emergence of India as a major economic power in the world happens to be one such idea”.

He dismantled the restrictive “license raj” which dictated the products factories could make and what types of bread could be sold, devalued the rupee to boost exports, opened key industrial sectors to private and foreign investment, and slashed taxes. The bold steps ushered in rapid growth, earning Singh the moniker of India’s economic “liberator”.

The same deft economic hand marked his first term as prime minister. He presided over an economy that grew at more than 8%, championed landmark initiatives such as the Indo-US civil nuclear deal which ended India’s nuclear isolation, and launched ambitious social welfare programmes. But his second term was marred by a string of massive corruption scandals that eroded public trust in his administration.

Those scandals led to accusations that Singh, despite being personally incorruptible, lacked the authority to control his coalition partners. His former adviser Sanjaya Baru wrote a tell-all memoir, saying it seemed Singh “would maintain the highest standards of probity in public life but would not impose this on others”. Singh’s seeming deference to Sonia Gandhi led to allegations that he was her “puppet”.

Singh, who is survived by his wife Gursharan Kaur and three daughters, famously described politics as “the art of the possible” and said toward the end of his second term as prime minister that “history will be kinder to me than the media”.