American politician (1924–2005)

Shirley Chisholm

Shirley Chisholm

Chisholm in 1972

Secretary of the House Democratic CaucusIn office

January 3, 1977 – January 3, 1981LeaderTip O’NeillPreceded byPatsy MinkSucceeded byGeraldine FerraroMember of the U.S. House of Representatives

from New York‘s 12th districtIn office

January 3, 1969 – January 3, 1983Preceded byEdna KellySucceeded byMajor OwensMember of the New York State AssemblyIn office

January 1, 1965 – December 31, 1968Preceded byThomas JonesSucceeded byThomas R. FortuneConstituency17th district (1965)

45th district (1966)

55th district (1967–1968) Personal detailsBorn

Shirley Anita St. Hill

(1924-11-30)November 30, 1924

Brooklyn, New York, U.S.DiedJanuary 1, 2005(2005-01-01) (aged 80)

Ormond Beach, Florida, U.S.Resting placeForest Lawn CemeteryPolitical partyDemocraticSpouses

- Conrad Chisholm

-

-

- (m. 1949; div. 1977)

- Arthur Hardwick Jr.

-

-

- (m. 1977; died 1986)

Education

Shirley Anita Chisholm (/ˈtʃɪzəm/ CHIZ-əm; née St. Hill; November 30, 1924 – January 1, 2005) was an American politician who, in 1968, became the first black woman to be elected to the United States Congress.[1] Chisholm represented New York’s 12th congressional district, a district centered in Bedford–Stuyvesant, Brooklyn[a] for seven terms from 1969 to 1983. In 1972, she became the first black candidate for a major-party nomination for President of the United States and the first woman to run for the Democratic Party‘s presidential nomination. Throughout her career, she was known for taking “a resolute stand against economic, social, and political injustices,”[2][3][4][5] as well as being a strong supporter of black civil rights and women’s rights.[6][7][8][9]

Born in Brooklyn, New York, she spent ages five through nine in Barbados, and she always considered herself a Barbadian American. She excelled at school and earned her college degree in the United States. She started working in early childhood education, and she became involved in local Democratic Party politics in the 1950s. In 1964, overcoming some resistance because she was a woman, she was elected to the New York State Assembly. Four years later, she was elected to Congress, where she led the expansion of food and nutrition programs for the poor and rose to party leadership. She retired from Congress in 1983 and taught at Mount Holyoke College while continuing her political organizing. Although nominated for the ambassadorship to Jamaica in 1993, health issues caused her to withdraw. In 2015, Chisholm was posthumously awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

Shirley Anita St. Hill was born to immigrant parents on November 30, 1924, in Brooklyn, New York City. She was of Afro-Guyanese and Afro-Barbadian descent.[10] She had three younger sisters,[11] two born within three years of her and one later.[12] Her father, Charles Christopher St. Hill, was born in British Guiana[13] before moving to Barbados.[12] He arrived in New York City via Antilla, Cuba, in 1923.[13] Her mother, Ruby Seale, was born in Christ Church, Barbados and arrived in New York City in 1921.[14]

Charles St. Hill was a laborer who worked in a factory that made burlap bags and as a baker’s helper. Ruby St. Hill was a skilled seamstress and domestic worker who experienced the difficulty of working outside the home while simultaneously raising her children.[15][16] As a consequence, in November 1929, when Shirley turned five, she and her two sisters were sent to Barbados on the MS Vulcania to live with their maternal grandmother, Emaline Seale.[16] Shirley later said, “Granny gave me strength, dignity, and love. I learned from an early age that I was somebody. I didn’t need the black revolution to teach me that.”[17] Shirley and her sisters lived on their grandmother’s farm in the Vauxhall village in Christ Church, where Shirley attended a one-room schoolhouse.[18] She returned to the United States in 1934, arriving in New York on May 19 aboard the SS Nerissa.[19] As a result of her time in Barbados, Shirley spoke with a West Indian accent throughout her life.[11] In her 1970 autobiography, Unbought and Unbossed, she wrote: “Years later I would know what an important gift my parents had given me by seeing to it that I had my early education in the strict, traditional, British-style schools of Barbados. If I speak and write easily now, that early education is the main reason.”[20] In addition, she belonged to the Quaker Brethren sect found in the West Indies, and religion became important to her; however, later in life, she attended services in a Methodist church.[21] As a result of her time on the island, and despite her U.S. birth, she always would consider herself a Barbadian American.[22]

Beginning in 1939, she attended Girls’ High School in the Bedford–Stuyvesant neighborhood of Brooklyn, a highly regarded, integrated school that attracted girls from throughout Brooklyn.[23] She did well academically at Girls’ High and was chosen to be vice president of the Junior Arista honor society.[24] She was accepted at and offered scholarships to Vassar College and Oberlin College, but the family could not afford the room-and-board costs to go to either school; instead, she selected Brooklyn College, where there was no charge for tuition and she could live at home and commute to the school.[24]

She earned her Bachelor of Arts from Brooklyn College in 1946, majoring in sociology and minoring in Spanish[25] (a language that she would employ at times during her political career).[26] She won prizes for her debating skills[15] and graduated cum laude.[27] During her time at Brooklyn College, she was a member of Delta Sigma Theta sorority and the Harriet Tubman Society.[28] As a member of the Harriet Tubman Society, she advocated for inclusion (specifically in terms of the integration of black soldiers in the military during World War II), the addition of courses that focused on African-American history and the involvement of more women in the student government.[29] However, this was not her first introduction to activism or politics. Growing up, she was surrounded by politics, as her father was an avid supporter of Marcus Garvey‘s and a dedicated supporter of the rights of trade union members.[29] She saw her community advocate for its rights as she witnessed the Barbados workers’ and anti-colonial independence movements.[29]

She met Conrad O. Chisholm in the late 1940s.[30] He had migrated to the United States from Jamaica in 1946, and he later became a private investigator who specialized in negligence-based lawsuits.[31] They married in 1949 in a large West Indian-style wedding.[31] She subsequently suffered two miscarriages, and, to their disappointment, the couple would have no children;[32] although, in the view of scholar Julie Gallagher, it is possible that her career goals played a role in this outcome as well.[33]: 395

After graduating from college, Chisholm began working as a teacher’s aide at the Mt. Calvary Child Care Center in Harlem.[34][33]: 395 She would work at the center in a teaching role from 1946 to 1953.[34][15] Meanwhile, she was furthering her education,[15] attending classes at night and earning her Master of Arts in childhood education from Teachers College of Columbia University in 1951.[34]

From 1953 to 1954, she was director of the Friend in Need Nursery,[35] located in Brownsville, Brooklyn,[15] and then, from 1954 to 1959, she was director of the Hamilton-Madison Child Care Center,[35] located in Lower Manhattan.[15] At the latter, there were 130 children between the ages of three and seven, and 24 employees reported to her.[35] From 1959 to 1964, she was an educational consultant for the Division of Day Care in New York City’s Bureau of Child Welfare.[15] There, she was in charge of supervising ten day-care centers as well as starting up new ones.[36] She became an authority on early education and child-welfare issues.[15]

Chisholm entered the world of politics in 1953, when she joined Wesley “Mac” Holder’s effort to elect Lewis Flagg Jr. to the bench as the first black judge in Brooklyn.[33]: 395 The Flagg election group later transformed into the Bedford–Stuyvesant Political League (BSPL).[33]: 395 The BSPL pushed candidates to support civil rights, fought against racial discrimination in housing, and sought to improve economic opportunities and services in Brooklyn.[33]: 395 Chisholm eventually left the group around 1958 after clashing with Holder over Chisholm’s push to give female members of the group more input in decision-making.[33]: 395–396

She also worked as a volunteer for white-dominated political clubs in Brooklyn, like the Brooklyn Democratic Clubs and the League of Women Voters.[37][38] With the Political League, she was part of a committee that chose the recipient of its annual Brotherhood Award.[39] She also was a representative of the Brooklyn branch of the National Association of College Women.[40] Furthermore, within the political organizations that she joined, Chisholm sought to make meaningful changes to the structure and make-up of the organizations, specifically the Brooklyn Democratic Clubs, which resulted in her being able to recruit more people of color into the 17th District Club and, thus, local politics.[29]

In 1960, Chisholm joined a new organization, the Unity Democratic Club (UDC), led by former Flagg campaign member Thomas R. Jones.[33]: 396 The UDC’s membership was mostly middle class, racially integrated, and included women in leadership positions.[33]: 396 Chisholm campaigned for Jones, who lost the election for an assembly seat in 1960, but ran again two years later and won, becoming Brooklyn’s second black assemblyman.[33]: 396–397

“Young woman, what are you doing out here in this cold? Did you get your husband’s breakfast this morning? Did you straighten up your house? What are you doing running for office? This is something for men.”

—Chisholm relating what an older African-American man told her at a Brooklyn housing project in 1964 when she was collecting signatures for her nominating petition for state assembly. She calmly explained her experience and commitment to the community, and he ended up signing the petition.[41]

After Jones accepted a judicial appointment rather than seek reelection, Chisholm sought to run for his seat in the New York state assembly in 1964.[33]: 397 Chisholm faced resistance based on her sex, with the UDC hesitant to support a female candidate.[33]: 397 Chisholm chose to appeal directly to women, including using her role as Brooklyn branch president of Key Women of America to mobilize female voters.[33]: 398 Chisholm won the Democratic primary in June 1964.[33]: 398 She then won the seat in December with over 18,000 votes over Republican and Liberal Party candidates, neither of whom received more than 1,900 votes.[33]: 398

Chisholm reviewing political statistics in 1965

Chisholm was a member of the New York State Assembly from 1965 to 1968, sitting in the 175th, 176th and 177th New York State Legislatures. By May 1965, she had already been honored in a “Salute to Women Doers” affair in New York.[42] One of her early activities in the Assembly was to argue against the state’s literacy test requiring English, holding that just because a person “functions better in his native language is no sign a person is illiterate”.[43] By early 1966, she was a leader in a push by the statewide Council of Elected Negro Democrats for black representation on key committees in the Assembly.[44]

Her successes in the legislature included getting unemployment benefits extended to domestic workers.[45] She also sponsored the introduction of a SEEK program (Search for Education, Elevation and Knowledge) to the state, which provided disadvantaged students with the chance to enter college while receiving intensive remedial education.[45]

In August 1968, she was elected as the Democratic National Committeewoman from New York State.[46]

“Ladies and gentlemen, this is fighting Shirley Chisholm coming through.”

—Announcement made from a sound truck that drove up to housing projects in Brooklyn during her 1968 campaign.[47]

In 1968, Chisholm ran for the U.S. House of Representatives from New York’s 12th congressional district, which, as part of a court-mandated reapportionment plan, had been significantly redrawn to focus on Bedford–Stuyvesant and was thus expected to result in Brooklyn’s first black member of Congress.[48] (Adam Clayton Powell Jr. had, in 1945, become the first black member of Congress from New York City as a whole.) As a result of the redrawing, the white incumbent in the former 12th, Representative Edna F. Kelly, sought reelection in a different district.[49] Chisholm announced her candidacy around January 1968 and established some early organizational support.[48] Her campaign slogan was “Unbought and unbossed”.[46][50] In the June 18 Democratic primary, Chisholm defeated two other black opponents, State Senator William S. Thompson and labor official Dollie Robertson.[49] In the general election, she staged an upset victory[11] over James Farmer, the former director of the Congress of Racial Equality, who was running as a Liberal Party candidate with Republican support, winning by an approximately two-to-one margin.[46] Chisholm thereby became the first black woman elected to Congress,[46] and she was the only woman in the first-year class that year.[51]

Speaker of the House John W. McCormack assigned Chisholm to serve on the House Agriculture Committee. Given her urban district, she felt the placement was irrelevant to her constituents.[1] When Chisholm confided to Rebbe Menachem M. Schneerson that she was upset and insulted by her assignment, Schneerson suggested that she use the surplus food to help the poor and hungry. Chisholm subsequently met Bob Dole and worked to expand the food-stamp program. She later played a critical role in the creation of the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants and Children (WIC). Chisholm would credit Schneerson for the fact that so many “poor babies [now] have milk and poor children have food”.[52] Chisholm was then also placed on the Veterans’ Affairs Committee.[1] Soon after, she voted for Hale Boggs as House Majority Leader over John Conyers. As a reward for her support, Boggs assigned her to the much-prized Education and Labor Committee,[30] which was her preferred committee.[1] She was the third-highest-ranking member of this committee when she retired from Congress.

Initially, Chisholm only hired women for her office; half of them were black.[1] In later years, she did hire some men for both her Washington office and the one in her Brooklyn district.[53] Chisholm said that she had faced much more discrimination during her New York legislative career because she was a woman than for her race.[1]

Chisholm (seated, second from right) with fellow founding members of the Congressional Black Caucus in 1971

In 1971, Chisholm served as a founding member of both the Congressional Black Caucus and the National Women’s Political Caucus.[11][54] In January 1971, Chisholm was one of 74 U.S. representatives to co-sponsor the House version of the Health Security Act, a bipartisan universal healthcare bill that supported the creation of a government health insurance program to cover every person in America.[55]

In May 1971, Chisholm and fellow New York Congresswoman Bella Abzug introduced a bill to provide $10 billion in federal funds for child-care services by 1975.[56] A less expensive version introduced by Senator Walter Mondale[56] eventually passed the House and Senate as the Comprehensive Child Development Bill, but it was vetoed in December 1971 by President Richard Nixon, who said that it was too expensive and would undermine the institution of the family.[57]

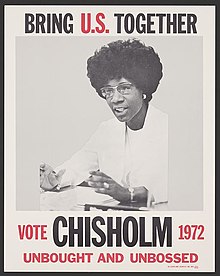

Shirley Chisholm 1972 presidential campaign poster

Chisholm began exploring her candidacy in July 1971 and formally announced her presidential bid on January 25, 1972,[1] in a Baptist church in her district in Brooklyn.[11] There, she called for a “bloodless revolution” at the forthcoming Democratic nominating convention for the 1972 U.S. presidential election.[11] Chisholm became the first African American to run for a major party’s nomination for President of the United States, making her also the first woman ever to run for the Democratic Party’s presidential nomination (U.S. Senator Margaret Chase Smith having previously run for the 1964 Republican presidential nomination).[1] In her presidential announcement, Chisholm described herself as representative of the people and offered a new articulation of American identity: “I am not the candidate of black America, although I am black and proud. I am not the candidate of the women’s movement of this country, although I am a woman and equally proud of that. I am the candidate of the people and my presence before you symbolizes a new era in American political history.”[58]

Her campaign was underfunded, only spending $300,000 in total.[1] She also struggled to be regarded as a serious candidate instead of as a symbolic political figure;[30] the Democratic political establishment ignored her, and her black male colleagues provided little support.[59] She later said, “When I ran for the Congress, when I ran for president, I met more discrimination as a woman than for being black. Men are men.”[15] In particular, she expressed frustration about the “black matriarch thing”, saying, “They think I am trying to take power from them. The black man must step forward, but that doesn’t mean the black woman must step back.”[11] Her husband, however, was fully supportive of her candidacy and said, “I have no hangups about a woman running for president.”[31] Security was also a concern, as, during the campaign, three confirmed threats were made against her life; Conrad Chisholm served as her bodyguard until U.S. Secret Service protection was given to her in May 1972.[60]

Chisholm skipped the initial March 7 New Hampshire contest, instead focusing on the March 14 Florida primary, which she thought would be receptive due to its “blacks, youth, and a strong women’s movement”.[1] But, due to organizational difficulties and Congressional responsibilities, she only made two campaign trips there and ended with 3.5 percent of the vote for a seventh-place finish.[1][61] Chisholm had difficulties gaining ballot access, but campaigned or received votes in primaries in fourteen states.[1] Her largest number of votes came in the June 6 California primary, where she received 157,435 votes for 4.4 percent and a fourth-place finish, while her best percentage in a competitive primary came in the May 6 North Carolina contest, where she got 7.5 percent for a third-place finish.[61] Overall, she won 28 delegates during the primaries process itself.[1][62] Chisholm’s base of support was ethnically diverse and included the National Organization for Women. Betty Friedan and Gloria Steinem attempted to run as Chisholm delegates in New York.[1] Altogether, during the primary season, she received 430,703 votes, which was 2.7 percent of the total of nearly 16 million cast and represented seventh place among the Democratic contenders.[61] In June, Chisholm became the first woman to appear in a United States presidential debate.[63]

At the 1972 Democratic National Convention in Miami Beach, Florida, there were still efforts taking place by the campaign of former Vice President Hubert Humphrey to stop the nomination of Senator George McGovern for president. After that failed and McGovern’s nomination was assured, as a symbolic gesture, Humphrey released his black delegates to Chisholm.[64] This, combined with defections from disenchanted delegates from other candidates, as well as the delegates that she had won in the primaries, gave her a total of 152 first-ballot votes for the presidential nomination during the July 12 roll call.[1] (Her precise total was 151.95.[61]) Her largest support overall came from Ohio, with 23 delegates (slightly more than half of them white),[65] even though she had not been on the ballot in the May 2 primary there.[1][61] Her total gave her fourth place in the roll-call tally, behind McGovern’s winning total of 1,728 delegates.[61] Chisholm said that she ran for office “in spite of hopeless odds … to demonstrate the sheer will and refusal to accept the status quo”.[30]

It is sometimes stated that Chisholm won a primary in 1972, or won three states overall, with New Jersey, Louisiana and Mississippi being so identified.[66] None of these fit the usual definition of winning a plurality of the contested popular vote or delegate allocations at the time of a state primary, caucus or state convention. In the June 6 New Jersey primary, there was a complex ballot that featured both a delegate-selection vote and a non-binding, non-delegate-producing “beauty contest” presidential preference vote.[67] In the delegate-selection vote, Democratic front-runner McGovern defeated his main rival at that point, Humphrey, and won the large share of available delegates.[67] Of the Democratic candidates, only Chisholm and former North Carolina governor Terry Sanford were on the statewide preference ballot.[67] Sanford had withdrawn from the contest three weeks earlier.[68] In that non-binding preference tally, which the Associated Press described as “meaningless”,[69] Chisholm received the majority of votes:[67] 51,433, which was 66.9 percent.[61] During the actual balloting at the national convention, Chisholm received votes from only 4 of New Jersey’s 109 delegates, with 89 going to McGovern.[61]

In the May 13 Louisiana caucuses, there was a battle between forces of McGovern and Alabama governor George Wallace; nearly all of the delegates chosen were those who identified as uncommitted, many of them black.[70] Leading up to the convention, McGovern was thought to control 20 of Louisiana’s 44 delegates, with most of the rest uncommitted.[71] During the actual roll call at the national convention, Louisiana passed at first, then cast 18.5 of its 44 votes for Chisholm, with the next-best finishers being McGovern and Senator Henry M. Jackson with 10.25 each.[61][65] As one delegate explained, “Our strategy was to give Shirley our votes for sentimental reasons on the first ballot. However, if our votes would have made the difference, we would have gone with McGovern.”[65] In Mississippi, there were two rival party factions that each selected delegates at their own state conventions and caucuses: “regulars”, representing the mostly white state Democratic Party, and “loyalists”, representing many blacks and white liberals.[71][72] Each slate professed to be largely uncommitted, but the regulars were thought to favor Wallace and the loyalists McGovern.[72] By the time of the national convention, the loyalists were seated following a credentials challenge, and their delegates were characterized as mostly supporting McGovern, with some support for Humphrey.[71] During the convention, some McGovern delegates became angry about what they saw as statements from McGovern that backed away from his commitment to end U.S. involvement in Southeast Asia, and cast protest votes for Chisholm as a result.[73] During the actual balloting, Mississippi went in the first half of the roll call, and cast 12 of its 25 votes for Chisholm, with McGovern coming next with 10 votes.[61]

During the campaign, the German filmmaker Peter Lilienthal shot the documentary film Shirley Chisholm for President for the German television channel ZDF.[74]

Chisholm at the 1984 Democratic National Convention

Chisholm created controversy when she visited rival and ideological opposite George Wallace in the hospital soon after his shooting in May 1972, during the presidential primary campaign. Several years later, when Chisholm worked on a bill to give domestic workers the right to a minimum wage, Wallace helped gain votes from enough Southern congressmen to push the legislation through the House.[75]

From 1977 to 1981, during the 95th Congress and 96th Congress, Chisholm served as Secretary of the Democratic Caucus.[76]

Throughout her tenure in Congress, Chisholm worked to improve opportunities for inner-city residents.[33]: 393, 402–403 She supported spending increases for education, health care and other social services.[33]: 403 She was very concerned with instances of discrimination against women, especially those against impoverished women.[27] She also focused on land rights for Native Americans.[27]

In the area of national security and foreign policy, Chisholm worked for the revocation of Internal Security Act of 1950.[77] She opposed the American involvement in the Vietnam War and the expansion of weapon developments.[33]: 403–404 She was a vocal opponent of the U.S. military draft.[33]: 403–404 During the Jimmy Carter administration, she called for better treatment of Haitian refugees.[78]

She was a forceful advocate for the Equal Rights Amendment, believing that the initial value of passing it would be in the social and psychological effects that it would have more than any economic or legal impact.[79] She did not want the amendment modified to incorporate a provision that would permit laws that purportedly protected the health and safety of women, saying such a modification would continue a traditional avenue of discrimination against women.[80] Regarding a specific argument made along these lines, that the amendment would require women to be subject to the draft, Chisholm was unperturbed, saying that if there was a draft, women could serve, and that some larger, stronger women might perform better in infantry roles than some smaller, weaker men.[81]

At the same time, Chisholm was aware of how much of second-wave feminism in the United States focused on the concerns of middle-class white women, such as the adoption of the term “Ms.“[33]: 410 At the 1973 convention of the National Women’s Political Caucus, Chisholm said that “women of color” were faced with “double discrimination” that especially affected them economically, and that the women’s movement needed to make changes to reflect better such women and their concerns.[33]: 410–411 Scholar Julie Gallagher has written that Chisholm’s pressure in this regard did make some difference in the focus of the women’s movement later in the 1970s.[33]: 411

Chisholm’s first marriage ended in a divorce, which was granted on February 4, 1977, in the Dominican Republic.[82] Later that year, on November 26,[82] she married Arthur Hardwick Jr., a former New York State Assemblyman whom Chisholm had known when they both served in that body and who was now a Buffalo, New York, liquor-store owner.[15] The ceremony was held in a Buffalo-area hotel.[82] She indicated that while her legal name was now Hardwick, she would continue to use Chisholm in politics.[82] She began spending some of her time in Buffalo, which brought some political criticism that she was being inattentive to her district.[83]

By the mid- to late-1970s, there was growing dissatisfaction with Chisholm among some liberals in New York state and city politics, who felt that Chisholm too often sided with Democratic party bosses over liberal, black or feminist challengers.[84] Instances of her doing this included supporting the incumbent conservative Democrat John J. Rooney over the liberal antiwar activist Allard Lowenstein in a 1972 congressional primary; failing to support Bella Abzug‘s primary campaigns for U.S. senator in 1976 and New York mayor in 1977; failing to support the young feminist Elizabeth Holtzman‘s successful primary challenge to the aging congressional incumbent Emanuel Celler in 1972; and remaining neutral during longtime African-American civil rights leader and elected official Percy Sutton‘s bid in the 1977 mayoral primary, followed by endorsing Ed Koch in a runoff.[85][86] This dissatisfaction was exemplified by a long 1978 piece published in The Village Voice, titled “Chisholm’s Compromises: Politics and the Art of Self-Interest” and written by former UDC ally Andrew W. Cooper and Voice investigative reporter Wayne Barrett.[84] Similarly, The Amsterdam News ran an editorial about the “Chisholm problem”.[86] Chisholm defended herself by saying that she was selecting those candidates who could best protect the interests of, and produce government benefits for, her constituents, but critics said that her behavior put the lie to the “unbossed” part of her slogan.[84][86] To her biographer Barbara Winslow, Chisholm, being black and a woman, had no natural political base, and she was likely siding with the Democratic machine in order to give herself a secure spot from which to speak out on the provocative progressive messages that she wanted to put forth.[85] A later analysis in The Washington Post framed the matter by saying that, despite the celebrity stemming from her presidential campaign, “Chisholm has been a lonely politician. Her unpredictability has led to an isolation that has been augmented by her pride and paranoia.”[86]

Hardwick was badly injured in an April 1979 automobile accident.[86][27] Desiring to take care of her husband, and also dissatisfied with the course of liberal politics in the wake of the Reagan Revolution, Chisholm decided to leave Congress.[15] The possibility that she would be challenged in a Democratic primary election may have also been a factor in her decision.[83] She announced her retirement in February 1982, saying that she looked forward to “a more private life”. She further expressed that the Reagan administration was “not responsive to our constituency. The constituency is going to be more voluble and demanding, and I find myself in a position where I can’t help them.”[87] She also lamented the tactics of the Christian right, which she said made potent use of the media and the symbols of family, morality and the national flag to quiet dissatisfaction in the people.[87] But, overall, Chisholm felt that press reports had overemphasized her political dissatisfaction in her retirement calculus; fundamentally, she said in September 1982, “I’ve been so obsessed with politics and the desire to help my people all these years, I’ve never had time to think about my personal life. I think the accident was an instrument, God’s way of making me reassess my life.”[27] She said she never intended to spend her whole career in politics and looked forward to a return to teaching.[27]

Shirley Chisholm (center) with Representative Edolphus Towns (left) and his wife, Gwen Towns (right)

External videos Shirley Chisholm Memorial Service, Congressional Black Caucus, February 15, 2005, C-SPAN[88]

External videos Shirley Chisholm Memorial Service, Congressional Black Caucus, February 15, 2005, C-SPAN[88]

After leaving Congress in January 1983, Chisholm made her home in Williamsville, New York, a suburb of Buffalo.[89][90] Wanting to resume her career in education, she had hoped to be named a college president, in particular of Medgar Evers College in Brooklyn or of City College of New York in Manhattan, but past political opponents were influential in the selection processes and she received neither post.[91] Similarly, a move to make her New York City Schools Chancellor was blocked by teachers-union head, and longtime foe, Albert Shanker, and she withdrew from consideration for that position.[91]

However, she was offered a dozen possible teaching positions at colleges.[91] She accepted being named to the Purington Chair at the all-women Mount Holyoke College in Massachusetts, a position that she held for the next four years.[92] She was not a member of any particular department, but was able to teach classes in a variety of areas;[93] those previously holding the professorship included W. H. Auden, Bertrand Russell and Arna Bontemps.[89] When questioned why she would want to teach at an institution with mostly affluent whites as students, she replied that she enjoyed the challenge of exposing them to both her feminist viewpoint and her background and experiences.[94] In addition, during this time, she spent the Spring 1985 semester as a visiting professor at the historically black women’s Spelman College in Atlanta.[21] At Spelman, she taught classes titled “Congress, Power and Politics”, where she sought to engage students in questions about representative government, and “History of the Black Woman in America”.[21]

In 1984, Chisholm and C. Delores Tucker co-founded an organization initially known as the National Black Women’s Political Caucus. This was established during the vice presidential campaign of Geraldine Ferraro. African-American women from various political organizations convened to set forth a political agenda emphasizing the needs of women of African descent. Chisholm was chosen as its first chair.[95] Creation of the group represented a split with an earlier organization, the National Black Women’s Political Leadership Caucus, which had been co-founded by Tucker in 1971. Following a protest by the earlier group, the new one changed its name to the National Political Congress of Black Women,[96] later simplified to the National Congress of Black Women.[97][98]

During those years, she continued to give speeches at colleges, by her own count visiting over 150 campuses since becoming nationally known.[90] She told students to avoid polarization and intolerance: “If you don’t accept others who are different, it means nothing that you’ve learned calculus.”[90] Continuing to be involved politically, she traveled to visit different minority groups and urge them to become a strong force at the local level.[90] She campaigned for Jesse Jackson during his 1984 and 1988 presidential campaigns.[99] In 1990, Chisholm, along with 15 other black women and men, formed African-American Women for Reproductive Freedom.[100]

Her husband, Arthur Hardwick, died in August 1986.[101] Chisholm moved to Florida in 1991.[15] In 1993, President Bill Clinton nominated her to be United States Ambassador to Jamaica, but she could not serve due to poor health, and the nomination was withdrawn.[102] In that same year, she was inducted into the National Women’s Hall of Fame.[103]

The inscription on Chisholm’s mausoleum, including her campaign slogan, “Unbought and Unbossed”

Chisholm died on January 1, 2005, at her home in Ormond Beach, Florida;[15] her health had been in decline after she had suffered a series of small strokes the previous summer.[30] At her funeral, held in Palm Coast, Florida, the minister said that Chisholm had brought about change because “she showed up, she stood up and she spoke up.”[104] She is buried in the Birchwood Mausoleum at Forest Lawn Cemetery in Buffalo, where the legend inscribed on her vault reads: “Unbought and Unbossed”.[105]

In February 2005, Shirley Chisholm ’72: Unbought and Unbossed, a documentary film,[106] aired on U.S. public television. It chronicled Chisholm’s 1972 bid for the Democratic presidential nomination. It was directed and produced by independent African-American filmmaker Shola Lynch. The film was featured at the Sundance Film Festival in 2004. On April 9, 2006, the film was announced as a winner of a Peabody Award.[107]

In 2014, the first biography of Chisholm for an adult audience was published, Shirley Chisholm: Catalyst for Change, by Brooklyn College history professor Barbara Winslow, who was also the founder and first director of the Shirley Chisholm Project. Until then, only several juvenile biographies had appeared.[108]

Chisholm’s speech “For the Equal Rights Amendment”, given in 1970, is listed as number 91 in American Rhetoric’s Top 100 Speeches of the 20th Century (listed by rank).[109][6]

The Shirley Chisholm Project on Brooklyn Women’s Activism (formerly known as the Shirley Chisholm Center for Research) exists at Brooklyn College to promote research projects and programs on women and to preserve Chisholm’s legacy.[110] The Chisholm Project also houses an archive as part of the Chisholm Papers in the college library Special Collections.[111][112]

In January 2018, Governor Andrew Cuomo announced his intent to build the Shirley Chisholm State Park, a 407-acre (165 ha) state park along 3.5 miles (5.6 km) of the Jamaica Bay coastline, adjoining the Pennsylvania Avenue and Fountain Avenue landfills south of Spring Creek Park‘s Gateway Center section. The state park was dedicated to Chisholm that September.[113][114] The park opened to the public on July 2, 2019.[115]

In April 2023, the Vauxhall Primary School in Christ Church, Barbados, which was built in 1976 to replace the school where Chisholm received her elementary education, was renamed the Shirley Chisholm Primary School. The renaming ceremony was attended by Chisholm’s relatives, and a plaque was unveiled by Barbados Prime Minister Mia Mottley, the island’s first female premier. The school’s Shirley Chisholm Memorial Garden contains a bust of Chisholm and a colorful mural showcasing her achievements.[116]

A memorial monument of Chisholm is planned for the entrance to Prospect Park in Brooklyn by Parkside Avenue station, designed by artists Amanda Williams and Olalekan Jeyifous.[117] After four years of delays and revisions, the project gained approval from the New York City Public Design Commission during 2023.[118]

The Shirley Chisholm Legacy Project, founded by Jacqueline Patterson, aims to advance climate justice for black communities through the Just Transition Framework. This initiative links frontline black leaders, especially women, with the necessary resources to drive systemic change from harmful extractive practices to an economy that acknowledges the principles of sustainable living. The project aims to address the interconnected challenges of environmental issues, poverty, racial discrimination and gender inequality.[119][120]

Chisholm’s legacy came into renewed prominence during the 2008 Democratic presidential primaries, when Barack Obama and Hillary Clinton staged their historic “firsts” battle – where the victor would either be the first major-party African-American nominee, or the first female nominee – with at least one observer crediting Chisholm’s 1972 campaign as having paved the way for both of them.[59]

Chisholm has been a major influence on other women of color in politics, among them California Congresswoman Barbara Lee, who stated in a 2017 interview that Chisholm had a profound impact on her career.[121] Lee had worked for Chisholm’s 1972 presidential campaign.[26]

By the time of the 50th anniversary of Chisholm entering Congress, The New York Times was headlining “2019 Belongs to Shirley Chisholm”, saying that “Chisholm was a one-woman precursor to modern progressive politics” and that she was “enjoying a resurgence of interest 14 years after her death”.[47]

Chisholm has also inspired Vice President Kamala Harris,[122] who recognized Chisholm’s presidential campaign by using similar typography and red-and-yellow color scheme in her own 2020 presidential campaign‘s promotional materials and logo.[123] Harris launched her presidential campaign 47 years to the day after Chisholm’s presidential campaign.[124]

Actress Uzo Aduba portrayed Chisholm in the FX on Hulu miniseries Mrs. America, released in April 2020, for which she won an Emmy Award for Outstanding Supporting Actress in a Limited Series.[125][126]

In November 2020, Danai Gurira was cast as Shirley Chisholm in The Fighting Shirley Chisholm, directed by Cherien Dabis, about her 1972 run for president.[127][128][129] However, as of 2024, the film had not appeared,[130] and it was still considered to be in development.[131]

Another film, Shirley, was announced in February 2021, with Regina King as Chisholm and John Ridley directing.[132] Also announced in the cast were Lance Reddick, Lucas Hedges, Amirah Vahn, André Holland, Christina Jackson, Michael Cherrie, Dorian Missick, W. Earl Brown and Terrence Howard.[133] Shirley was released on Netflix in March 2024.[130]

Chisholm was also heavily featured in Mel Brooks‘s 2023 satirical television series History of the World, Part II, played by Wanda Sykes. Segments throughout the series loosely detailed Chisholm’s presidential bid stylized as episodes of Shirley!, a fictional 1970s sitcom. The episodes “starred” other members of Chisholm’s family and friends, including Conrad Chisholm (Colton Dunn), Florynce Kennedy (Kym Whitley) and Ruby Seale (Marla Gibbs).[134]

- Presidential Medal of Freedom (posthumously awarded) by President Barack Obama at a ceremony in the White House.[135] – November 2015.

- William L. Dawson Award by the Congressional Black Caucus Foundation[136]– 1982

- In 1974, Chisholm was awarded an Honorary Doctor of Laws degree by Aquinas College and was their commencement speaker.[137]

- In 1975, Chisholm was awarded an Honorary Doctor of Laws degree by Smith College.[138]

- In 1981, Chisholm was awarded an Honorary Doctor of Laws degree by Mount Holyoke College.[139]

- In 1996, Chisholm was awarded an Honorary Doctor of Laws Degree by Stetson University, in Deland, Florida.[140]

- In 1991, Chisholm was the commencement speaker at East Stroudsburg University in East Stroudsburg, Pennsylvania, where she received the first-ever conferred honorary doctorate from the university. An annual ESU student award was created in her honor.[141]

- In 1993, she was inducted into the National Women’s Hall of Fame.[142]

- In 2002, scholar Molefi Kete Asante included Shirley Chisholm on his list of 100 Greatest African Americans.

- On January 31, 2014, the Shirley Chisholm Forever Stamp was issued.[143] It is the 37th stamp in the Black Heritage series of U.S. stamps.

- The Shirley Chisholm Living-Learning Community at Mount Holyoke College in South Hadley, Massachusetts is a residential hall floor in which students of African descent can choose to live.[144]

Chisholm wrote two autobiographies:

- Chisholm, Shirley (1970). Unbought and Unbossed. Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-395-10932-8Chisholm, Shirley (2010). Scott Simpson (ed.). Unbought and Unbossed: Expanded 40th Anniversary Edition. Take Root Media. ISBN 978-0-9800590-2-1

- Chisholm, Shirley (1973). The Good Fight. Harper Collins. ISBN 978-0-06-010764-2

- List of African-American United States representatives

- Politics of New York City

- United States House of Representatives

- Women in the United States House of Representatives

- ^ At various times, the district also included parts of the surrounding neighborhoods of Brownsville, Bushwick, Crown Heights and East New York. For her final two terms in office, the district stretched as far north as Newtown Creek.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Freeman, Jo (February 2005). “Shirley Chisholm’s 1972 Presidential Campaign”. University of Illinois at Chicago Women’s History Project. Archived from the original on November 11, 2014.

- ^ Fraser, Zinga A. (2022). “Beyond the Symbolism: Shirley Chisholm, Black Feminism, and Women’s Politics”. In Giles KN; Rachel Jessica Daniel; Laura L Lovett (eds.). It’s Our Movement Now: Black Women’s Politics and the 1977 National Women’s Conference. University Press of Florida. pp. 175–184. doi:10.5744/florida/9780813069487.003.0014. ISBN 978-0-8130-6948-7. Retrieved August 22, 2023.

- ^ Curwood, Anastasia (2015). “Black Feminism on Capitol Hill: Shirley Chisholm and Movement Politics, 1968–1984”. Meridians. 13 (1): 204–232. doi:10.2979/meridians.13.1.204. ISSN 1536-6936. JSTOR 10.2979/meridians.13.1.204. S2CID 142146607.

- ^ Winslow, Barbara (April 27, 2018). Shirley Chisholm: Catalyst for Change, 1926–2005 (1 ed.). Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780429493126. ISBN 978-0-429-49312-6. S2CID 259517966.

- ^ Guild, Joshua (2020), “11 To Make That Someday Come: Shirley Chisholm’s Radical Politics of Possibility”, Want to Start a Revolution?, New York University Press, pp. 248–270, doi:10.18574/nyu/9780814733127.003.0015, ISBN 978-0-8147-3312-7, retrieved August 22, 2023

- ^ a b Eidenmuller, Michael E. (August 10, 1970). “Shirley Chisholm – For the Equal Rights Amendment (Aug 10, 1970)”. American Rhetoric. Archived from the original on October 21, 2015. Retrieved October 27, 2015.

- ^ “Shirley Chisholm, “For the Equal Rights Amendment,” Speech Text”. Voices of Democracy. Retrieved August 22, 2023.

- ^ Curwood, Anastasia C. (2023). Shirley Chisholm: Champion of Black Feminist Power Politics. The University of North Carolina Press. doi:10.1353/book.109689. ISBN 978-1-4696-7119-2. S2CID 259517966.

- ^ Chisholm, Shirley (1983). “Racism and Anti-Feminism”. The Black Scholar. 14 (5): 2–7. doi:10.1080/00064246.1983.11414282. ISSN 0006-4246. JSTOR 41067044.

- ^ Brooks-Bertram and Nevergold, Uncrowned Queens, p. 146.

- ^ a b c d e f g Moran, Sheila (April 8, 1972). “Shirley Chisholm’s running no matter what it costs her”. The Free Lance-Star. Fredericksburg, Virginia. Associated Press. p. 16A. Archived from the original on October 18, 2020. Retrieved August 21, 2020.

- ^ a b Winslow, Shirley Chisholm, pp. 7–8.

- ^ a b “New York Passenger Lists, 1850 -1957 [database on-line]”. United States: The Generations Network. April 10, 1923. Archived from the original on October 7, 2009. Retrieved July 20, 2008.

- ^ “New York Passenger Lists, 1820–1957 [database on-line]”. United States: The Generations Network. March 8, 1921. Archived from the original on October 7, 2009. Retrieved July 7, 2008.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Barron, James (January 3, 2005). “Shirley Chisholm, ‘Unbossed’ Pioneer in Congress, Is Dead at 80”. The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 7, 2021. Retrieved February 12, 2017.

- ^ a b Winslow, Shirley Chisholm, p. 9.

- ^ Lesher, Stephan (June 25, 1972). “The Short, Unhappy Life of Black Presidential Politics, 1972” (PDF). The New York Times Magazine. p. 12. Archived from the original on December 7, 2021. Retrieved June 15, 2018.

- ^ Winslow, Shirley Chisholm, pp. 10–12.

- ^ “New York Passenger Lists, 1820–1957 [database on-line]”. United States: The Generations Network. May 19, 1934. Archived from the original on October 7, 2009. Retrieved July 20, 2008.

- ^ Chisholm, Unbought and Unbossed, pp. 7–8.

- ^ a b c Graham, Keith (February 6, 1985). “‘Catalyst’ still making sparks”. The Atlanta Constitution. pp. 1-B, 3-B – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Winslow, Shirley Chisholm, p. 5.

- ^ Shirley Chisholm, Unbought and Unbossed: Expanded 40th Anniversary Edition, Take Root Media, 2010, p. 38.

- ^ a b Winslow, Shirley Chisholm, p. 21.

- ^ Winslow, Shirley Chisholm, pp. 22, 24.

- ^ a b “Before Hillary Clinton, there was Shirley Chisholm”, Rajini Vaidyanathan BBC News, Washington, January 26, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f Duty, Juana E. (September 12, 1982). “Outspoken Shirley Chisholm retiring from politics”. The Indianapolis Star. Los Angeles Times. p. 2G – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ “Shirley Chisholm | C-SPAN.org”. www.c-span.org. Archived from the original on March 8, 2021. Retrieved April 30, 2020.

- ^ a b c d mosesm (May 24, 2012). “Shirley Chisholm, CUNY and U.S. History”. PSC CUNY. Archived from the original on April 20, 2020. Retrieved March 8, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e “Shirley Chisholm, first black woman elected to Congress, dies”. USA Today. Associated Press. January 2, 2005. Archived from the original on July 6, 2012. Retrieved September 11, 2017.

- ^ a b c “Conrad Chisholm Content To Be Candidate’s Husband”. Sarasota Journal. Associated Press. February 29, 1972. p. 3B. Archived from the original on October 16, 2020. Retrieved August 21, 2020.

- ^ Winslow, Shirley Chisholm, pp. 27–28, 34.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u Gallagher, Julie (2007). “Waging ‘The Good Fight’: The Political Career of Shirley Chisholm, 1953–1982”. The Journal of African American History. 92 (3). Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago: 392–416. doi:10.1086/JAAHv92n3p392. JSTOR 20064206. S2CID 140827104.

- ^ a b c Winslow, Shirley Chisholm, p. 26.

- ^ a b c Winslow, Shirley Chisholm, p. 28.

- ^ Winslow, Shirley Chisholm, p. 34.

- ^ Moran, Sheila (April 8, 1972). “Shirley Chisholm’s running no matter what it costs her”. The Free Lance–Star. Fredericksburg, Virginia. Associated Press. p. 16A. Archived from the original on October 18, 2020. Retrieved August 21, 2020.

- ^ mosesm (May 24, 2012). “Shirley Chisholm, CUNY and U.S. History”. PSC CUNY. Archived from the original on April 20, 2020. Retrieved April 20, 2020.

- ^ “Paragon ‘Brotherhood’ Meet: ‘Protest’ Group to Albany”. New York Age Defender. February 23, 1957. p. 4. Archived from the original on August 7, 2020. Retrieved November 18, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Randolph, Juanita (May 16, 1959). “Tops in Teens”. New York Age. p. 10. Archived from the original on August 7, 2020. Retrieved November 18, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Winslow, Shirley Chisholm, p. 44. See also Chisholm, Unbought and Unbossed, pp. 70–71.

- ^ “Women ‘Doers’ in Government, Community Service Acclaimed at ‘Salute’ Luncheon”. Pittsburgh Courier. NPI. May 15, 1965. p. 8. Archived from the original on August 7, 2020. Retrieved November 18, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ “Literacy Vote Test Is Made”. The Daily Messenger. Canandaigua, New York. United Press International. May 19, 1965. p. 12. Archived from the original on August 3, 2020. Retrieved November 18, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ “Travia, Negro Block Split on Meeting Results”. The Kingston Daily Freeman. Associated Press. January 6, 1966. p. 9. Archived from the original on August 7, 2020. Retrieved November 18, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b “Shirley Chisholm to speak at Hunter”. The Afro-American. Baltimore. February 5, 1971. p. 13. Archived from the original on October 29, 2020. Retrieved August 21, 2020.

- ^ a b c d Madden, Richard L. (November 6, 1968). “Mrs. Chisholm Defeats Farmer, Is First Negro Woman in House” (PDF). The New York Times. pp. 1, 25.

- ^ a b Steinhauer, Jennifer (July 6, 2019). “2019 Belongs to Shirley Chisholm”. The New York Times. p. 2 (Sunday Review).

- ^ a b Caldwell, Earl (February 26, 1968). “3 Negroes Weigh House Race in New Brooklyn 12th District” (PDF). The New York Times. p. 29. Archived from the original on December 7, 2021. Retrieved June 15, 2018.

- ^ a b Schanberg, Sydney H. (June 19, 1968). “Seymour and Cellar Win House Contests” (PDF). The New York Times. pp. 1, 31. Archived from the original on December 7, 2021. Retrieved June 15, 2018.

- ^ Landers, Jackson, ‘Unbought And Unbossed’: When a Black Woman Ran for the White House Archived August 10, 2020, at the Wayback Machine, Smithsonian Magazine, April 25, 2016

- ^ “CHISHOLM, Shirley Anita | United States House of Representatives: History, Art & Archives”. history.house.gov. Archived from the original on March 1, 2020. Retrieved February 23, 2020.

- ^ Telushkin, Joseph (2014). Rebbe: The Life and Teachings of Menachem M. Schneerson, the Most Influential Rabbi in Modern History. HarperCollins. pp. 13–14.

- ^ Winslow, Shirley Chisholm, p. 72.

- ^ Carlson, Coralie (January 3, 2005). “Pioneering Politician, Candidate Dies”. The Washington Post. Associated Press. p. A4. Archived from the original on October 27, 2017. Retrieved September 11, 2017.

- ^ Congressional Record: Proceedings and Debates of the 92nd Congress, First Session, Volume 117-Part 1; January 21, 1971 to February 1, 1971 (Pages 3 to 1338), Page 491.

- ^ a b “Mrs. Chisholm, Mrs. Abzug Introduce Child Care Bill” (PDF). The New York Times. Associated Press. May 18, 1971. Archived from the original on December 7, 2021. Retrieved June 15, 2018.

- ^ Rosenthal, Jack (December 10, 1971). “President Vetoes Child Care Plan As Irresponsible” (PDF). The New York Times. p. 1. Archived from the original on December 7, 2021. Retrieved June 15, 2018.

- ^ “The First Black Woman Presidential Candidate | Equality Archive”. Equality Archive. October 21, 2015. Archived from the original on November 17, 2018. Retrieved November 16, 2018.

- ^ a b Clack, Gary (February 27, 2008). “Shirley Chisholm broke ground before Barack Obama and Hillary Clinton”. Seattle Post-Intelligencer. Archived from the original on December 7, 2021. Retrieved May 30, 2010.

- ^ Winslow, Shirley Chisholm, p. 124.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Presidential Elections 1789–2008 (5th ed.). Washington, D.C.: CQ Press. 2005. pp. 366–369 (primaries), 652–653 (convention).

- ^ House resolution 97, Recognizing Contributions, Achievements, and Dedicated Work of Shirley Anita Chisholm, [Congressional Record: June 12, 2001 (House). Page H3019-H3025] From the Congressional Record Online via GPO Access [wais.access.gpo.gov] [DOCID:cr12jn01-85]

- ^ “Opinion”. NBC News. June 23, 2019. Archived from the original on June 29, 2019. Retrieved June 28, 2019.

- ^ Delaney, Paul (July 11, 1972). “Humphrey Blacks to Vote For Mrs. Chisholm First” (PDF). The New York Times. p. 1. Archived from the original on December 7, 2021. Retrieved June 15, 2018.

- ^ a b c Petit, Michael D. (July 22, 1972). “Delegates were ready to switch to save day”. The Afro-American. Baltimore. p. 2. Archived from the original on December 7, 2021. Retrieved August 21, 2020.

- ^ See for example this 2016 piece in The Nation or this 2012 piece in Salon.

- ^ a b c d Sullivan, Ronald (June 7, 1972). “Dakotan Beats Humphrey By a Big Margin in Jersey” (PDF). The New York Times. p. 1. Archived from the original on November 9, 2021. Retrieved June 15, 2018.

- ^ “Sanford Is Withdrawing From N.J.” The Times-News. Hendersonville, North Carolina. Associated Press. May 13, 1972. p. 12. Archived from the original on October 10, 2021. Retrieved August 21, 2020.

- ^ Mears, Walter R. (June 7, 1972). “McGovern Leads In California”. Bangor Daily News. Associated Press. pp. 1, 3.

- ^ “Wallace Gets 29 Tennessee Delegates”. The News and Courier. Charleston, South Carolina. Associated Press. May 14, 1972. p. 4D.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b c Chaze, William L. (July 8, 1972). “Southern Delegates Aren’t Solid”. The Times-News. Hendersonville, North Carolina. Associated Press. p. 7. Archived from the original on October 29, 2020. Retrieved August 21, 2020.

- ^ a b Reed, Roy (June 4, 1972). “Democratic Factions in Mississippi Urged to Settle Delegate Fight” (PDF). The New York Times. p. 53. Archived from the original on December 7, 2021. Retrieved June 15, 2018.

- ^ Watkins, Wesley (July 13, 1972). “Seniority seen as key to party merger”. Delta Democrat-Times. Greenville, Mississippi. p. 3. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved March 6, 2016 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ “Shirley Chisholm for President” (in German). filmportal.de. Retrieved December 8, 2021. Expand ‘Alle Credits’ to see commissioning by ZDF.

- ^ “Shirley Chisholm, pioneer in Congress, dies at 80”. NBC News. January 4, 2005. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved May 2, 2015.

- ^ “Women Elected to Party Leadership Positions”. Women in Congress. U.S. House of Representatives. Archived from the original on July 30, 2008. Retrieved December 15, 2008.

- ^ “Congress Honors Shirley Chisholm, the First African American Woman Representative”. Democracy Now!. Archived from the original on November 15, 2007.

- ^ Babcock, Charles R. (June 18, 1980). “Rep. Chisholm Asks Equity For Haiti’s Black Refugees”. Washington Post.

- ^ Sherrill, Robert (September 20, 1970). “That Equal-Rights Amendment – What, Exactly, Does It Mean?”. The New York Times Magazine. pp. 25ff.

- ^ “House Debates Amendment to End Sex Discrimination”. The New York Times. October 7, 1971. p. 43.

- ^ Fraser, C. Gerald (March 30, 1972). “Mrs. Chisholm Starts Campaign in State”. The New York Times. p. 33.

- ^ a b c d “Who’s in the News: It’s Still Chisholm”. The Lexington Leader. November 28, 1977. p. A-2 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Winslow, Shirley Chisholm, p. 147.

- ^ a b c Winslow, Shirley Chisholm, pp. 143–144.

- ^ a b Winslow, Shirley Chisholm, p. 145.

- ^ a b c d e Trescott, Jacqueline (June 6, 1982). “Shirley Chisholm in Her Season of Transition”. The Washington Post.

- ^ a b Perlez, Jane (February 11, 1982). “Mrs. Chisholm Plans to Retire from Congress”. The New York Times. p. B3.

- ^ “Shirley Chisholm Memorial Service”. C-SPAN. February 15, 2005. Archived from the original on May 8, 2017. Retrieved April 9, 2017.

- ^ a b Haberman, Clyde; Johnston, Laurie (August 3, 1982). “New York Day by Day: Shirley Chisholm’s New Job”. The New York Times. Archived from the original on August 5, 2016. Retrieved February 12, 2017.

- ^ a b c d Manuel, Diane Casselberry (December 13, 1983). “For Shirley Chisholm, life in academia is hardly sedentary”. The Christian Science Monitor. Archived from the original on September 20, 2015. Retrieved March 29, 2014.

- ^ a b c Winslow, Shirley Chisholm, pp. 150–151.

- ^ “Shirley Chisholm: Activist, Professor, and Congresswoman”. College Street Journal. Mount Holyoke College. January 28, 2005. Archived from the original on March 29, 2014.

- ^ “Professor”. Rome News-Tribune. Associated Press. November 15, 1982. p. 5. Archived from the original on October 28, 2020. Retrieved August 21, 2020.

- ^ Winslow, Shirley Chisholm, pp. 151–152.

- ^ “WOMANPOWER”. Washington Post. August 6, 1984. ISSN 0190-8286. Archived from the original on December 7, 2018. Retrieved December 6, 2018.

- ^ Meyer, Jimmy Elaine Wilkinson (2003). “National Black Women’s Political Leadership Caucus”. In Mjagkij, Nina (ed.). Organizing Black America: An Encyclopedia of African American Associations. Routledge. pp. 368–369. ISBN 1135581231.

- ^ Feitelberg, Rosemary (August 4, 2021). “National Congress of Black Women to Honor B Michael”. WWD. Retrieved December 8, 2021.

- ^ “ABOUT”. ncbwhmc. Retrieved December 8, 2021.

- ^ Sandberg, Betsy (February 18, 1988). “Shirley Chisholm Sees Pat Robertson as Threat to Minorities, Women”. Schenectady Gazette. p. 39. Archived from the original on August 19, 2021. Retrieved August 21, 2020.

- ^ Kathryn Cullen-DuPont (August 1, 2000). Encyclopedia of women’s history in America. Infobase Publishing. p. 6. ISBN 978-0-8160-4100-8. Archived from the original on October 22, 2020. Retrieved February 4, 2012.

- ^ “Obituaries: Arthur Hardwick Jr”. New York Daily News. United Press International. August 21, 1986. p. C13 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ “Statement on the Withdrawal of the Nomination of Shirley Chisholm To Be Ambassador to Jamaica”. The White House. October 13, 1993. Archived from the original on February 25, 2016. Retrieved March 16, 2014.

- ^ National Women’s Hall of Fame, Women of the Hall – Shirley Chisholm

- ^ “Shirley Chisholm”. The Economist. February 2, 2005. ISSN 0013-0613. Archived from the original on December 29, 2019. Retrieved December 29, 2019.

- ^ Nussbaumer, Newell (October 1, 2021). “Request for Proposals: Shirley Chisholm statue to be built, and installed at Forest Lawn”. Buffalo Rising. Retrieved December 8, 2021.

- ^ Steve Skafte (January 18, 2004). “Chisholm ’72: Unbought & Unbossed (2004)”. IMDb. Archived from the original on October 9, 2019. Retrieved June 30, 2018.

- ^ 65th Annual Peabody Awards Archived March 14, 2015, at the Wayback Machine, May 2006.

- ^ Winslow, Shirley Chisholm, p. 153.

- ^ Eidenmuller, Michael E. (February 13, 2009). “Top 100 Speeches of the 20th Century by Rank”. American Rhetoric. Archived from the original on October 27, 2015. Retrieved October 27, 2015.

- ^ “Shirley Chisholm Center for Research on Women”. Brooklyn College. Archived from the original on March 28, 2014. Retrieved March 28, 2014.

- ^ “Shirley Chisholm Project on Brooklyn Women’s Activism Content”. Brooklyn College. Archived from the original on March 28, 2014. Retrieved March 28, 2014.

- ^ “The Shirley Chisholm Project”. Archived from the original on November 11, 2018. Retrieved November 10, 2018.

- ^ Plitt, Amy (September 5, 2018). “Brooklyn will get 407-acre state park dedicated to Shirley Chisholm”. Curbed NY. Archived from the original on September 5, 2018. Retrieved September 6, 2018.

- ^ “Shirley Chisholm State Park in Brooklyn to be city’s largest state park”. News 12 Brooklyn. September 5, 2018. Archived from the original on September 7, 2018. Retrieved September 6, 2018.

- ^ “The city’s largest state park opens in East New York”. Brooklyn Eagle. July 2, 2019. Archived from the original on August 10, 2019. Retrieved July 29, 2019.

- ^ Henry, Anesta (April 5, 2023). “Vauxhall Primary School now Shirley Chisholm Primary”. Barbados Today. Retrieved March 29, 2024.

- ^ Steinhauer, Jillian (April 23, 2019). “The Shirley Chisholm Monument in Brooklyn Finds Its Designers”. The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 14, 2020. Retrieved February 25, 2020.

- ^ Small, Zachary (July 17, 2023). “City Approves Design for Shirley Chisholm Monument in Prospect Park”. The New York Times.

- ^ Richardson, Elizabeth Paige (March 27, 2024). “5 Organizations That Celebrate Shirley Chisholm’s Legacy”. Ebony.

- ^ Worland, Justin (February 21, 2024). “Jacqui Patterson’s Revolutionary Approach to Climate Justice”. TIME.

- ^ “Street Heat w/ Congresswoman Barbara Lee & Linda Sarsour, episode #45 of Politically Re-Active with W. Kamau Bell and Hari Kondabolu on Earwolf”. www.earwolf.com. Archived from the original on February 28, 2018. Retrieved February 27, 2018.

- ^ “‘We Stand On The Shoulders Of Shirley Chisholm’: Brooklyn Political Powerhouse Serves As Source Of Inspiration For Sen. Kamala Harris”. August 12, 2020. Retrieved December 17, 2021.

- ^ O’Kane, Caitlin (January 21, 2019). “Kamala Harris’ 2020 presidential campaign logo pays tribute to Shirley Chisholm”. CBS News. Archived from the original on January 23, 2019. Retrieved January 23, 2019.

- ^ “Branding the women running for president in 2020”. Fastcompany.com. January 30, 2019. Archived from the original on February 3, 2019. Retrieved February 4, 2019.

- ^ Malkin, Marc (July 7, 2020). “Listen: Uzo Aduba on Playing Political Pioneer Shirley Chisholm in ‘Mrs. America'”. Variety. Archived from the original on July 12, 2020. Retrieved July 12, 2020.

- ^ White, Abbey (September 21, 2020). “Uzo Aduba Thanks Women of ‘Mrs. America’ and Shirley Chisholm in Emmys Acceptance Speech”. The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on October 5, 2020. Retrieved September 21, 2020.

- ^ Hipes, Patrick (November 11, 2020). “Danai Gurira To Star In ‘The Fighting Shirley Chisholm’; Cherien Dabis To Direct Retooled Pic”. Deadline. Archived from the original on November 12, 2020. Retrieved November 11, 2020.

- ^ Jackson, Angelique (November 11, 2020). “Danai Gurira to Play Pioneering Presidential Candidate Shirley Chisholm in New Film”. Variety. Archived from the original on November 11, 2020. Retrieved November 11, 2020.

- ^ “Danai Gurira to Star in Film of Presidential Candidate Shirley Chisholm”. TheWrap. November 11, 2020. Archived from the original on November 11, 2020. Retrieved November 11, 2020.

- ^ a b Pina, Christy (February 19, 2024). “Regina King Fights to Make a Difference in ‘Shirley’ Trailer”. Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved April 1, 2024.

- ^ “In development: More at IMDbPro: The Fighting Shirley Chisholm”. IMDb. Retrieved April 1, 2024.

- ^ “Regina King to Play Shirley Chisholm in ‘Shirley’ from John Ridley”. The Hollywood Reporter. February 17, 2021. Archived from the original on February 17, 2021. Retrieved February 17, 2021.

- ^ Grobar, Matt (December 16, 2021). “‘Shirley’: Lance Reddick, Lucas Hedges, André Holland, Terrence Howard & More Board Regina King Film As It Heads To Netflix”. Deadline Hollywood. Retrieved December 16, 2021.

- ^ Lloyd, Robert (March 6, 2023). “‘History of the World, Part II’ review: An homage to Mel Brooks”. L.A. Times. Retrieved March 11, 2023.

- ^ Phil Helsel – “Obama honoring Spielberg, Streisand and more with medal of freedom,” Archived November 25, 2015, at the Wayback Machine NBC News, November 24, 2015. Retrieved November 25, 2015

- ^ “Past Phoenix Award Honorees (1996 – 2018)”. https://s7.goeshow.com/cbcf/annual/2020/documents/CBCF_ALC_-_Phoenix_Awards_Dinner_Past_Winners.pdf

- ^ “Past Commencement Speakers and Honorary Degree Recipients”. Aquinas College (Michigan). Archived from the original on March 28, 2014. Retrieved March 28, 2014.

- ^ “Honorary Degrees”. Smith College. Archived from the original on March 27, 2014. Retrieved March 27, 2014.

- ^ “Commencement Address, the Genre”. Harvard Magazine. July 1, 2000.

- ^ “Stetson University Commencement Program”. Stetson University. May 12, 1996.

- ^ “Shirley Chisholm To Address E. Stroudsburg Graduates”. Archived from the original on September 11, 2017. Retrieved September 11, 2017.

- ^ “Home – National Women’s Hall of Fame”. National Women’s Hall of Fame. Archived from the original on March 20, 2015. Retrieved September 11, 2017.

- ^ “Scott new Issues Update”. Linn’s Stamp News. 87 (4455): 60–61. March 17, 2014. ISSN 0161-6234.

- ^ “Living-Learning Communities | Mount Holyoke College”. October 26, 2015. Archived from the original on December 20, 2019. Retrieved September 11, 2019.

- Brooks-Bertram, Peggy; Nevergold, Barbara A. (2009). Uncrowned Queens, Volume 3: African American Women Community Builders of Western New York. In Commemoration of the Centennial of the Niagara Movement. Buffalo, New York. ISBN 978-0-9722977-2-1.{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

- Curwood, Anastasia C. (2023). Shirley Chisholm: Champion of Black Feminist Power Politics. The University of North Carolina Press. doi:10.1353/book.109689. ISBN 978-1-4696-7119-2. S2CID 259517966.

- Winslow, Barbara (2014). Shirley Chisholm: Catalyst for Change. Lives of American Women. Boulder, Colorado: Westview Press. ISBN 978-0-8133-4769-1.

Attribution

This article incorporates material from the Citizendium article “Shirley Chisholm“, which is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License but not under the GFDL.

- Fitzpatrick, Ellen (2016). The Highest Glass Ceiling: Women’s Quest for the American Presidency. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674088931. LCCN 2015045620.

- Howell, Ron (2018). Boss of Black Brooklyn: The Life and Times of Bertram L. Baker. Bronx, New York: Fordham University Press. ISBN 9780823280995. OCLC 1073190427.

Wikiquote has quotations related to Shirley Chisholm.

- Appearances on C-SPAN

- Finding Aid for the Shirley Chisholm ’72 Collection held by the Brooklyn College Library Archives and Special Collections

- Video of Shirley Chisholm declaring presidential bid, January 25, 1972 on YouTube

- Shirley Chisholm’s oral history Video excerpts at The National Visionary Leadership Project

- Shirley Chisholm at the National Women’s History Museum

- United States Congress. “Shirley Chisholm (id: C000371)”. Biographical Directory of the United States Congress.

- Chisholm speech on the Equal Rights Amendment

- Chisholm ’72 – Unbought & Unbossed PBS American Documentary | POV documentary by Shola Lynch

- Chisholm ’72 – Unbought & Unbossed Women Make Movies documentary by Shola Lynch

- Feature on Shirley Chisholm, with writing from Gloria Steinem and video clips from Chisholm ’72 Unbought & Unbossed, by the International Museum of Women.

New York State Assembly Preceded by

Member of the New York Assembly

from King‘s 17th district

1965 Constituency abolished New constituency Member of the New York Assembly

from the 45th district

1966 Succeeded by

Preceded by

Member of the New York Assembly

from the 55th district

1967–1968 Succeeded by

U.S. House of Representatives Preceded by

Member of the U.S. House of Representatives

from New York’s 12th congressional district

1969–1983 Succeeded by

Party political offices Preceded by

Secretary of the House Democratic Caucus

1977–1981 Succeeded by

Retrieved from “https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Shirley_Chisholm&oldid=1261797090“