Anand Gopal We should look first at the context in Syria before the revolution. The Assad regime had co-opted and eradicated the Left over fifty years, so what remained of the Syrian left was not rooted in working-class communities, and left-wing language was alien to these communities. Of course, Syria is hardly unique here — this is the story the world over.

Beginning in the 1990s, the regime allowed Islamic discourse to pervade society as part of its neoliberal turn. It encouraged the proliferation of Islamic charities to carry out the duties once performed by the state. Around the same time, millions of Syrians went as migrants to work in the Gulf and returned with a more Islamic outlook.

So by 2011, political Islam had become an authentic mode of expression among the Syrian working class. Still, at the outset of the revolution, the protesters were demanding a secular, democratic state. However, from the very beginning, there were two currents within the uprising. The majority were working-class people, often living in shanty towns ringing major cities or in small provincial towns. Their demands were for political freedom and a better livelihood. And a minority were middle- and upper-middle-class activists, often with university degrees, who focused primarily on demands for political freedom and saw class-based demands as secondary or irrelevant. This latter group was tapped into international NGO networks and adopted the Western neoliberal language of human rights and individual rights.

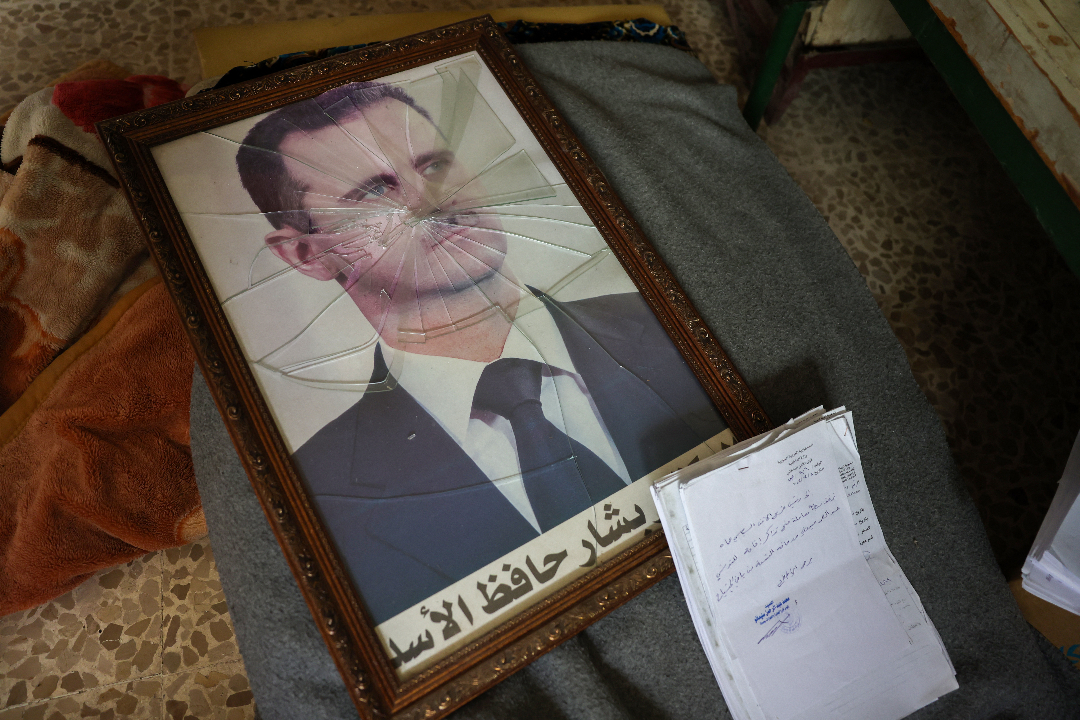

As the revolution wore on, and as towns and cities became liberated from the Assad regime, these two currents moved in different directions. The secular FSA rebels were corrupt and ineffective, and they did not offer an ideology that could paint for the poor and working class a positive vision of a different kind of society, where people’s needs would be met. It was the Islamists who offered a coherent program to respond to these grievances. They distinguished themselves from the secular rebels by being far less corrupt, and in areas they controlled, they prioritized issues like bread distribution. This is one important reason Islamists became hegemonic in the revolution.

So the dominance of Islamism in the revolution was not simply because of outside intervention — although foreign states, especially Turkey and Qatar, certainly pushed things along in that direction. It was due, ultimately, to the nature of the Assad regime and to the class divisions within the uprising itself.

There are few meaningful left-wing groups anywhere in the Middle East, and the reason for that is partly due to the failures of the Left, partly because of state repression, and partly because of the changing political economies. That means the Western left should not apply purity tests, but should analyze conditions on the ground based on a realistic understanding of the context. The Islamist rebels themselves are a mixed bag; some are truly reactionary, while others have moderated themselves and are meaningful vehicles for national liberation.